Introduction

This document briefly outlines the essential steps in the process of making genetic variant calls, and recommends tools that have gained community acceptance for this purpose. It is assumed that the purpose of the study is to detect short germline or somatic variants in a single sample. Recommended coverage for acceptable quality of calls in a research setting is around 30-50x for whole genome and 70-100x for exome sequencing, but lower coverage is discussed as well.

The procedures outlined below are recommendations to the H3ABioNet groups planning to do variant calling on human genome data, and are not meant to be prescriptive. Our goal is to help the groups set up their procedures and workflows, and to provide an overview of the main steps involved and the tools that can be used to implement them. For optimizing a workflow or an individual analysis step, the reader is referred to 1,2,3.

Glossary of associated terms and jargon

The table below (partly borrowed from the GATK dictionary 4 ) provides definitions of the basic terms used.

- Adapters

- Short nucleotide sequences added on to the ends of the DNA fragments that are to be sequenced 5 ,6,7). Functions:

- permit binding to the flow cell;

- allow for PCR enrichment of adapter-ligated DNA only;

- allow for indexing or “barcoding” of samples, so multiple DNA libraries can be mixed together into 1 sequencing lane.

- Genetic variant

- This can be:

- single nucleotide variation (SNV)

- small (<10 nt) insertions/deletions (indels)

- copy number variation (outside the scope of this document)

- Lane

- The basic machine unit for sequencing. The lane reflects the basic independent run of an NGS machine. For Illumina machines, this is the physical sequencing lane.

- Library

- A unit of DNA preparation that at some point is physically pooled together. Multiple lanes can be run from aliquots from the same library. The DNA library is the natural unit that is being sequenced. For example, if the library has limited complexity, then many sequences are duplicated and will result in a high duplication rate across lanes. See 8 for more details.

- NGS

- Next generation sequencing.

- WGS

- Whole Genome Sequencing.

- Sample

- A single individual, such as human CEPH NA12878. Multiple libraries with different properties can be constructed from the original sample DNA source. Here we treat samples as independent individuals whose genome sequence we are attempting to determine. From this perspective, tumor/normal samples are different despite coming from the same individual.

- SNV

- Single nucleotide variant.

- In a non-coding region

- In a coding region:

- synonymous

- nonsynonymous

- missense

- nonsense

- Functional Equivalence specifications 9

- Specifications intended to eliminate batch effects and promote data interoperability by standardizing pipeline implementations: used tools, versions of these tools, and versions of reference genomic files. Large genomic databases, like gnomAD and TOPmed are being processed by pipelines adhering to these specifications.

- Functional equivalence 9

- Two variant calling pipelines are functionally equivalent if they can be run independently on the same raw WGS data to produce aligned files (BAM or CRAM files) that yield genome variation maps (VCF files) that have >98% similarity when analyzed by the same variant caller(s).

Procedural steps

The publication by 10 provides a good discussion of the common tools and approaches for variant calling. Also see the older 11.

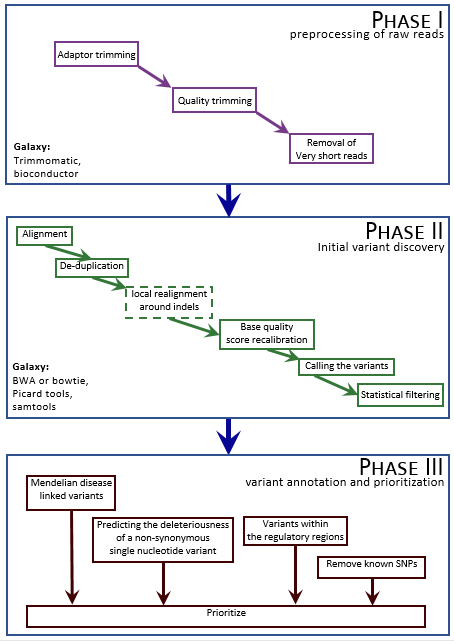

The figure below depicts the essential steps of the pipeline, which are detailed in the subsequent sections.

|

|---|

| Figure 1: Steps in the variant calling workflow |

Important note

The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) distributed by the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT (see http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/) is a commonly used framework and toolbox for many of the tasks described below. In its latest 4.0 release, the GATK is now completely open source. While we recommend GATK tools for many of the tasks, we try also to provide alternatives for those organizations that cannot or do not wish to use GATK (i.e for licensing reasons with older GATK versions). Please also note that while the key analysis steps remain the same, the GATK4 is intended to become a spark-based rewrite of GATK3. Many GATK4 tools come in spark-capable or non-spark-capable modes, and can run locally, on a Spark cluster or on Google Cloud Dataproc 12. There are some differences in invocation highlighted below, and where tools names have changed this is also indicated. A better introduction to the GATK3 is found here: https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/documentation/quickstart?v=3 and to the GATK4 is found here https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/documentation/quickstart?v=4 . Their computational performance is discussed here 1.

Phase 1: Preprocessing of the raw reads

The following steps prepare reads for analysis and must be performed in sequence.

Step 1.1: Adapter trimming

Sequencing facilities usually produce read files in fastq format 13, which contain a base sequence and a quality score for each base in a read. Usually the adapter sequences have already been removed from the reads, but sometimes bits of adapters are left behind, anywhere from 90% to 20% of the adapter length. These need to be removed from the reads. This can be done using your own script based on a sliding window algorithm. A number of tools will also perform this operation: Trimmomatic 14, Fastx-toolkit (fastx_clipper), Bioconductor (ShortRead package), Flexbar 15, as well as a number of tools listed on BioScholar 16 and Omics tools 17 databases.

Selection of the tool to use depends on the amount of adapter sequences leftover in the data. This can be assessed manually by grepping for parts of known adapter sequences on the command line.

Step 1.2: Quality trimming

Once the adapters have been trimmed, it is useful to inspect the quality of reads in bulk, and try to trim low quality nucleotides 18. Also, frequently the quality tends to drop off toward one end of the read. FASTQC 19 and PrinSeq 20 will show that very nicely . These read ends with low average quality can then be trimmed, if desired, using Trimmomatic 14, FASTX-Toolkit fastq_quality_filter, PrinSeq, or SolexaQA 21.

Step 1.3: Removal of very short reads

Once the adapter remnants and low quality ends have been trimmed, some reads may end up being very short (i.e. <20 bases). These short reads are likely to align to multiple (wrong) locations on the reference, introducing noise into the variation calls. They can be removed using PrinSeq, Trimmomatic (using the MINLEN option), or a simple in-house script. Minimum acceptable read length should be chosen based on the length of sequencing fragment: longer for longer fragments, shorter for shorter ones – it is a matter of some experimentation with the data.

The three pre-processing steps above can be parallelized by chunking the initial fastq file (hundreds of millions of reads, up to 50-150 G of hard disk space per file depending on sequencing depth) into several files that can be processed simultaneously. The results can then be combined.

Phase 2: Initial variant discovery

Analysis proceeds as a series of the following sequential steps.

Step 2.1 Alignment

Reads need to be aligned to the reference genome in order to identify the similar and polymorphic regions in the sample. As of 2016, the GATK team recommends their b37 bundle as the standard reference for Whole Exome and Whole Genome Sequencing analyses pending the completion of the GRcH38/Hg38 bundle 22. However, the 2018 functional equivalence specifications recommends the GRCh38DH from the 1000 Genomes project 9. Either way, a number of aligners can perform the alignment task.

Among these, BWA MEM 23 and bowtie2 24 have become trusted tools for short reads Illumina data, because they are accurate, fast, well supported, and open-source. Combined with variant callers, different aligners can offer different performance advantages with respect to SNPs, InDels and other structural variants, benchmarked in works like 23,25,26. Functional equivalence specifications recommends BWA-MEM v0.7.15 in particular (with at least the following parameters -K 100000000 -Y, and without -M so that split reads are marked as supplementary reads in congruence with BAM specification ).

The output file is usually in a binary BAM format 27, still taking tens or hundreds of Gigabytes of hard disk space. The alignment step tends to be I/O intensive, so it is useful to place the reference onto an SDD, as opposed to HDD, to speed up the process. The alignment can be easily parallelized by chunking the data into subsets of reads and aligning each subset independently, then combining the results.

Step 2.2: De-duplication

The presence of duplicate reads in a sequencing project is a notorious problem. The causes are discussed in a blog post by Eric Vallabh Minikel (2012) 28. Duplicately sequenced molecules should not be counted as additional evidence for or against a putative variant – they must be removed prior to the analysis. A number of tools can be used including: samblaster 29, sambamba 30, the commercial novosort from the novocraft suit 31, Picard, and FASTX-Toolkit has fastx_collapser for this purpose. Additionally, MarkDuplicates is shipped as part of GATK4, but is called from Picard tools 32 in older GATK releases. For functional equivalence 9, it is recommended to use Picard tools v2.4.1.

De-duplication can also be performed by a simple in-house written Perl script.

Step 2.3 Artifact removal: local realignment around indels

Some artifacts may arise due to the alignment stage, especially around indels where reads covering the start or the end of an indel are often incorrectly mapped. This results in mismatches between the reference and reads near the misalignment region, which can easily be mistaken for SNPs. Thus, the realignment stage aims to correct these artifacts by transforming those regions with misalignment due to indels into reads with a consensus indel for correct variant calling.

Realignment can be accomplished using the GATK IndelRealigner 33 (https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/documentation/tooldocs/3.8-0/org_broadinstitute_gatk_tools_walkers_indels_IndelRealigner.php ). Alternatives include Dindel 34 (https://github.com/genome/dindel-tgi ) and SRMA 35 (https://github.com/nh13/SRMA ).

The inclusion of the realignment stage in a variant calling pipeline depends on the variant caller used downstream. This stage might be of value when using non-haplotype-aware variant caller like the GATK’s UnifiedGenotyper 36. However, if the tool used for variant calling is haplotype-aware like Platypus 37, FreeBayes 38 or the HaplotypeCaller 39, then it is not needed nor recommended. The GATK recommendations starting from their 3.6 release onwards, and the guidelines for functional equivalence 9 also vote against this stage.

Ultimately however, characteristics of the dataset at hand would dictate whether realignment and other clean-up stages are needed. Ebbert et al paper for example argues against PCR duplicates removal 40, while Olson et al recommends all the stages of clean up applied to the dataset at hand 41. Some experimentation is therefore recommended when handling real datasets.

Step 2.4: Base quality score recalibration

Base quality scores, which refer to the per-base error estimates assigned by the sequencing machine to each called base, can often be inaccurate or biased. The recalibration stage aims to correct for these errors via an empirical error model built based on the characteristics of the data at hand 33. The quality score recalibration can be performed using GATK’s BQSR protocol 33, which is also the recommendation for functional equivalence, along with specific reference genome files 9. For speed up of analysis, and if using GATK v4, one may skip the PrintReads step and pass the output from BaseRecalibrator to the HaplotypeCaller directly. Bioconductor’s ReQON is an alternative tool 42 for this purpose.

Step 2.5 Calling the variants

There is no single “best” approach to capture all the genetic variations. For germline variants, 10 suggest using a consensus of results from three tools:

- CRISP 43,

- HaplotypeCaller 36 from the GATK, and

- mpileup from SAMtools (tutorial is available on the ANGUS site, Michigan State university http://ged.msu.edu/angus/tutorials-2012/snp_tutorial.html).

Recently, MuTect2 was added as a variant discovery tool to the GATK specifically for cancer variants. MuTect2 calls somatic SNPs and indels by combining the original MuTect 44 with the HaplotypeCaller. The HaplotypeCaller relies on diploid assumption, while MuTect2 allows for different allelic fractions for each variant. This makes the caller useful in tumor variant discovery. Joint calling (GVCF generation) is not available in MuTect2.

The variant calls are usually produced in the form of VCF files 45, occupying much smaller size than the BAMs generating them.

Step 2.6 Statistical filtering

The VCF files resulting from the previous steps frequently have many sites that are not really genetic variants, but rather machine artifacts that make the site statistically non-reference. In small studies, hard filtering of variants based on annotations of genomic context is typically sufficient

While, it requires expertise to define appropriate filtering thresholds, Heng Li provides some general guidelines in this paper 46. For experiments with a sufficiently large number of samples (30 or more), the GATK team designed the Variant Quality Score Recalibrator (VQSR) protocol to separate out the false positive machine artifacts from the true positive genetic variants using a Gaussian Mixture model based on the learned annotations of known datasets 33. A full tutorial is posted on GATK forums:

http://gatkforums.broadinstitute.org/discussion/39/variant-quality-score-recalibration-vqsr

Phase 3: Variant annotation and prioritization

This last preliminary stage is highly dependent on the study design and objectives, so only a brief coverage is provided herein.

Annotation and prioritization

This phase serves to select those variants that are of particular interest, depending on the research problem at hand. The methods are specific to the problem, thus we do not elaborate on them, and only provide a list of some commonly used tools below:

- Generating variant and sample-level annotations, and performing many other exploratory and filtration analysis types: Hail 47

- Exploring and prioritizing genetic variation in the the context of human disease: GEMINI 48

- Mendelian disease linked variants: VAR-MD, KGGSeq, FamSeq 49.

- Predicting the deleteriousness of a non-synonymous single nucleotide variant: dbNSFP, HuVariome, Seattle-Seq, ANNOVAR, VAAST, snpEff

- Identifying variants within the regulatory regions: RegulomeDB 50

H3ABioNet Accreditation Exercise

H3ABioNet Next Gen Training dataset

Practice data set for Variant Calling is available here

These are synthetic data, generated using the NEAT simulator51 to produce synthetic reads with “golden” variants inserted into the reference genome before “sequencing”. This practice dataset was generated as WES for chromosome 1 at 50X, with mutation rates of 0.0005 and sequencing error rates at 0.005. Also posted is the reference that was used to generate the data, along with the golden vcf. Finaly, posted are all the SNP and Indel files from the GATK bundle that were used to call variants to check concordance with GATK.

H3ABionet Next Gen Accreditation Questions

The following are questions to keep in mind when running the NextGen Workflow during the H3ABioNet accreditation exercise. Use them to plan your work in a way that would allow gathering the necessary information for your final report. The report should not be limited to only providing brief answers to these questions; it is expected to be a well-rounded description of the process of running the workflow, and of the results. Please note that only Phase I and Phase II of the variant calling SOP need to be performed.

Nature of the input dataset

- Was the input dataset of sufficiently good quality to perform the analysis?

- How did the reads’ quality and GC content affect the way analysis was run?

Operational questions

- At each step of the workflow, describe which software was used and why:

- Was the choice affected by the nature and/or quality of the reads?

- Was the choice made due to the time and cost of the analysis?

- What are the accuracy and performance considerations for the chosen piece of software?

- For each software, describe which input parameters were chosen, and why:

- Was the choice affected by the nature and/or quality of the reads?

- Did the available hardware play a role in the parameter choice?

- How did the purpose of the study affect the parameter choice?

- For each step of the workflow, how do you know that it completed successfully and that the results are usable for the next step?

Runtime analysis

This is useful information for making predictions for the clients and collaborators

- How much time and disk space did each step of the workflow take?

- How did the underlying hardware perform? Was it possible to do other things, or run other analyses on the same computer at the same time?

Analyzing the results

- How many variants were called with sufficient confidence to be included in further analyses? Are the results good and trustworthy, and can you estimate the sensitivity and selectivity of the analysis? How do you know the workflow completed successfully and the results are worth analyzing further?

- How many variants were located in intronic, exonic, or in non-genic regions? Put this in context of the nature of the input dataset as described in the README.

- How many variants were found in dbSNP and how many were unique to your sample? What does it mean?

- What is the fraction of simple variants (SNPs, small indels) versus complex variants (translocations, inversions, etc.)? How is this influenced by your choice of software and parameters?

- What would be the next steps for your analysis, given this information?

Appendices

Useful Resources

Examples of complete implementations of a variant calling pipeline:

- The Broad institute WDL reference implementations of the GATK best practices- here

- The H3ABioNet CWL implementation of the best practices (GATK3.5)- here

- A configurable Swift-t implementation (different tools, versions and options can be interchanged, so it is easy to confirm to functional equivalence specifications9 )- here

The GATK Resource Bundle52

The GATK resource bundle is a collection of standard files for working with human resequencing data with the GATK. Until the Hg38 bundle is complete, the b37 resources remain the standard data. To access the bundle on the FTP server, use the following login credentials:

Location: ftp.broadinstitute.org/bundle/b37

Username: gsapubftp-anonymous

Password:

Or, simply download using:

wget -r ftp://gsapubftp-anonymous@ftp.broadinstitute.org/bundle/b37

List of Tools

Alphabetized list of recommended tools

- ANNOVAR————————————————–http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/ Utilizes update-to-date information to generate gene-based, region-based and filter-based functional annotations of genetic variants detected from diverse genomes.

Usage

-

Annotate the variants in ex1.human file and classify them as intergenic, intronic, non-synonymous SNP, frameshift deletion, large-scale duplication, etc. The ex1.human file is in text format, one variant per line. The annotation procedure takes seconds on a typical modern computer.

perl annotate_variation.pl -geneanno example/ex1.human humandb/ -

Download cytogenetic band annotation databases from the UCSC Genome Browser and save it to the humandb/ directory as hg18_cytoBand.txt file, then annotate variants in ex1.human file and identify the cytogenetic band for these variants.

perl annotate_variation.pl -downdb cytoBand humandb/ perl annotate_variation.pl -regionanno -dbtype cytoBand example/ex1.human humandb/ -

Download 1000 Genome Projects allele frequency annotations, then identify a subset of variants in ex1.human that are not observed in 1000G CEU populations and those that are observed with allele frequencies.

perl annotate_variation.pl -downdb 1000g humandb/ perl annotate_variation.pl -filter -dbtype 1000g_ceu example/ex1.human humandb/

- Bed tools————————————————————-http://bedtools.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features.

Filtering SNPs

To remove known SNPs, use intersectBed (bedtools). Known SNPs can be downloaded from Ensembl or NCBI/UCSC (eg. dbSNP)

intersectBed -a accepted_hits.raw.filtered.vcf \

-b Mus_musculus.NCBIM37.60.bed \

-wo \

> filteredSNPs.vcf

- Bioconductor—————————————————————————http://bioconductor.org/ Provides tools for the analysis and comprehension of high-throughput genomic data. Bioconductor uses the R statistical programming language, and is open source and open development.

Sequence trimming

Use trimLRPatterns for adapter trimming. From http://manuals.bioinformatics.ucr.edu/home/ht-seq:

# Create sample sequences.

myseq <-DNAStringSet(c("CCCATGCAGACATAGTG", "CCCATGAACATAGATCC", "CCCGTACAGATCACGTG"));

names(myseq) <- letters[1:3];

# Remove the specified R/L-patterns. The number of maximum mismatches can be specified

# for each pattern individually. Indel matches can be specified with the arguments:

# with.Lindels and with.Rindels.

trimLRPatterns(Lpattern ="CCC", Rpattern="AGTG", subject=myseq, max.Lmismatch = 0.33,

max.Rmismatch = 1)

# To remove partial adapters, the number of mismatches for all possible partial matches

# can be specified by providing a numeric vector of length nchar(mypattern).

# The numbers specifiy the number of mismatches for each partial match.

# Negative numbers are used to prevent trimming of a minimum fragment length,

# e.g. most terminal nucleotides.

trimLRPatterns(Lpattern = "CCC", Rpattern="AGTG", subject=myseq,

max.Lmismatch=c(0,0,0), max.Rmismatch=c(1,0,0))

# With the setting 'ranges=TRUE' one can retrieve the corresponding

# trimming coordinates.

trimLRPatterns(Lpattern = "CCC", Rpattern="AGTG", subject=myseq,

max.Lmismatch=c(0,0,0), max.Rmismatch=c(1,0,0), ranges=T)

Base quality score recalibration

Use ReQON to recalibrate quality of nucleotides for aligned sequencing data in BAM format: http://bioconductor.org/packages/2.12/bioc/html/ReQON.html See ReQON tutorial for detailed examples of usage: http://bioconductor.org/packages/devel/bioc/vignettes/ReQON/inst//doc/ReQON.pdf

- blat—————————————————————-http://genome.ucsc.edu/FAQ/FAQblat.html ————————————————http://genome.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/help/blatSpec.html

Blat is an alignment tool like BLAST, but it is structured differently. On DNA, Blat works by keeping an index of an entire genome in memory. From a practical standpoint, Blat has several advantages over BLAST:

- speed (no queues, response in seconds) at the price of lesser homology depth

- the ability to submit a long list of simultaneous queries in fasta format

- five convenient output sort options

- a direct link into the UCSC browser

- alignment block details in natural genomic order

- an option to launch the alignment later as part of a custom track

Usage

blat <database> <query> [-ooc=11.ooc] output.psl

Database and query are each either a .fa , .nib or .2bit file, or a list these files.

The option -ooc=11.ooc tells the program to load over-occurring 11-mers from an external file. This will increase the speed by a factor of 40 in many cases, but is not required.

- Bowtie2———————————————http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml An ultrafast and memory-efficient tool for aligning sequencing reads to long reference sequences. It is particularly good at aligning reads of about 50 up to 100s or 1,000s of characters to relatively long (e.g. mammalian) genomes.

Usage

bowtie2 [options]* -x <bt2-idx> {-1 <m1> -2 <m2> | -U <r>} -S [<sam>]

-x <bt2-idx> -- The basename of the index for the reference genome. The basename is the name of any of the index files up to but not including the final .1.bt2 / .rev.1.bt2 / etc. bowtie2 looks for the specified index first in the current directory, then in the directory specified in the BOWTIE2_INDEXES environment variable.

-1 <m1> -- Comma-separated list of files containing mate 1s (filename usually includes _1), e.g. -1 flyA_1.fq,flyB_1.fq. Sequences specified with this option must correspond file-for-file and read-for-read with those specified in <m2>. Reads may be a mix of different lengths. If - is specified, bowtie2 will read the mate 1s from the "standard in" or "stdin" filehandle.

-2 <m2> -- Comma-separated list of files containing mate 2s (filename usually includes _2), e.g. -2 flyA_2.fq,flyB_2.fq. Sequences specified with this option must correspond file-for-file and read-for-read with those specified in <m1>. Reads may be a mix of different lengths. If - is specified, bowtie2 will read the mate 2s from the "standard in" or "stdin" filehandle.

-U <r> -- Comma-separated list of files containing unpaired reads to be aligned, e.g. lane1.fq,lane2.fq,lane3.fq,lane4.fq. Reads may be a mix of different lengths. If - is specified, bowtie2 gets the reads from the "standard in" or "stdin" filehandle.

-S <sam> -- File to write SAM alignments to. By default, alignments are written to the "standard out" or "stdout" filehandle (i.e. the console).

- BWA——————————————————————————http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/ Burrows-Wheeler Alignment Tool. A software package for mapping low-divergent sequences against a large reference genome, such as the human genome. It consists of three algorithms: BWA-backtrack, BWA-SW and BWA-MEM. The first algorithm is designed for Illumina sequence reads up to 100bp, while the rest two for longer sequences ranged from 70bp to 1Mbp. BWA-MEM and BWA-SW share similar features such as long-read support and split alignment, but BWA-MEM, which is the latest, is generally recommended for high-quality queries as it is faster and more accurate. BWA-MEM also has better performance than BWA-backtrack for 70-100bp Illumina reads.

Usage

Index database sequences:

bwa index ref.fa

Align 70bp-1Mbp query sequences with the BWA-MEM algorithm:

bwa mem ref.fa reads.fq > aln-se.sam #Single end reads

bwa mem ref.fa read1.fq read2.fq > aln-se.sam #For functional equivalence 9, add the options: -K 100000000 -Y

Find the SA coordinates of the input reads.

bwa aln ref.fa short_read.fq > aln_sa.sai

Generate alignments in the SAM format given single-end reads shorter than ~ 70bp

bwa aln ref.fa short_reads.fq > reads.sai

bwa samse ref.fa reads.sai short_reads.fq > aln-se.sam

Generate alignments in the SAM format given paired-end reads shorter than ~70bp.

bwa aln ref.fa read1.fq > read1.sai; bwa aln ref.fa read2.fq > read2.sai

bwa sampe ref.fa read1.sai read2.sai read1.fq read2.fq > aln-pe.sam

- FASTX-Toolkit——————————————————-http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/ A collection of command line tools for Short-Reads FASTA/FASTQ files preprocessing.

fastq_quality_filter

Filters sequences based on quality. http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/commandline.html#fastq_quality_filter_usage

fastq_quality_filter [-q N] [-p N] [-z] [-i INFILE] [-o OUTFILE]

[-q N] = Minimum quality score to keep.

[-p N] = Minimum percent of bases that must have [-q] quality.

[-z] = Compress output with GZIP.

[-i INFILE] = FASTA/Q input file. default is STDIN.

[-o OUTFILE] = FASTA/Q output file. default is STDOUT.

fastx-collapser

Collapses identical sequences in a FASTQ/A file into a single sequence). http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/commandline.html#fastx_collapser_usage

fastx_collapser [-i INFILE] [-o OUTFILE]

- Flexbar———————————————————- https://github.com/seqan/flexbar Flexbar — flexible barcode and adapter removal. Flexbar is a software to preprocess high-throughput sequencing data efficiently. It demultiplexes barcoded runs and removes adapter sequences. Trimming and filtering features are provided. Flexbar increases mapping rates and improves genome and transcriptome assemblies. It supports next-generation sequencing data from Illumina, Roche 454, and the SOLiD platform. Recognition is based on exact overlap sequence alignment.

Usage

flexbar -t target -r reads [-b barcodes] [-a adapters] [options]

Mandatory parameters:

input file with reads

input format of reads

target name for output prefix

- GATK————————————————————————http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/ Genome Analysis Toolkit - a software package developed at the Broad Institute to analyse next-generation resequencing data. The toolkit offers a wide variety of tools, with a primary focus on variant discovery and genotyping as well as strong emphasis on data quality assurance. Its robust architecture, powerful processing engine and high-performance computing features make it capable of taking on projects of any size.

There is a slight change when calling tools from either GATK version:

GATK3 invocation:

java -jar <jvm args like -Xmx4G go here> GenomeAnalysisTK.jar -T <ToolName>

GATK4 invocation:

gatk [--java-options <jvm args like -Xmx4G go here>] <ToolName> [GATK args go here]

BQSR http://gatkforums.broadinstitute.org/discussion/44/base-quality-score-recalibration-bqsr

The tools in this package recalibrate base quality scores of sequencing-by-synthesis reads in an aligned BAM file. After recalibration, the quality scores in the QUAL field in each read in the output BAM are more accurate in that the reported quality score is closer to its actual probability of mismatching the reference genome. Moreover, the recalibration tool attempts to correct for variation in quality with machine cycle and sequence context, and by doing so provides not only more accurate quality scores but also more widely dispersed ones. The system works on BAM files coming from many sequencing platforms: Illumina, SOLiD, 454, Complete Genomics, Pacific Biosciences, etc. Invocation based on recommended functional equivalent parameters 9 is below:

java -Xmx4g -jar GenomeAnalysisTK.jar \

-T BaseRecalibrator

-R ${ref_fasta} \

-I ${input_bam} \

-O ${recalibration_report_filename} \

-knownSites "Homo_sapiens_assembly38.dbsnp138.vcf" \

-knownSites "Mills_and_1000G_gold_standard.indels.hg38.vcf.gz" \

-knownSites "Homo_sapiens_assembly38.known_indels.vcf.gz"

To create a recalibrated BAM you can use GATK’s PrintReads (GATK3), or ApplyBQSR (GATK4) with the engine on-the-fly recalibration capability. Here is the recommended command line to do so while complying with the functional equivalence specification 9:

java -jar GenomeAnalysisTK.jar \

-T PrintReads \

-R reference.fasta \

-I input.bam \

-BQSR recalibration_report.grp \

-o output.bam

-SQQ 10 -SQQ 20 -SQQ 30 \

--disable_indel_quals

IndelRealigner

Performs local realignment of reads to correct misalignments due to the presence of indels. Realginemet is no longer needed with a haplotype-aware variant caller like the HaplotypeCaller 39 , but this is provided for completion https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/documentation/tooldocs/3.8-0/org_broadinstitute_gatk_tools_walkers_indels_IndelRealigner.php

java -Xmx4g -jar GenomeAnalysisTK.jar \

-T IndelRealigner \

-R ref.fasta \

-I input.bam \

-targetIntervals intervalListFromRTC.intervals \

-o realignedBam.bam \

[-known /path/to/indels.vcf]

HaplotypeCaller

Call SNPs and indels simultaneously via local de-novo assembly of haplotypes in an active region. https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/documentation/tooldocs/3.8-0/org_broadinstitute_gatk_tools_walkers_haplotypecaller_HaplotypeCaller.php

java -jar GenomeAnalysisTK.jar

-T HaplotypeCaller \

-R reference/human_g1k_v37.fasta \

-I sample1.bam [-I sample2.bam ...] \

--dbsnp dbSNP.vcf \

-stand_call_conf [50.0] \

-stand_emit_conf 10.0 \

[-L targets.interval_list] \

-o output.raw.snps.indels.vcf

MuTect2

Call SNPs and indels simultaneously via local de-novo assembly of haplotypes, combining the MuTect genotyping engine and the assembly-based machinery of HaplotypeCaller. For cancer variant discovery. Tumor/Normal or Normal-only calls.

java -jar GenomeAnalysisTK.jar

-T MuTect2 \

-R reference.fa \

-I:tumor tumor.bam \

-I:normal normal.bam \

[--dbsnp sbSNP.vcf] \

[--cosmic COSMIC.vcf] \

[-L targets.interval_list] \

-o output.vcf

UnifiedGenotyper

A variant caller which unifies the approaches of several disparate callers – Works for single-sample and multi-sample data. In most applications, the recommendation is to use the newer HaplotypeCaller https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/documentation/tooldocs/3.8-0/org_broadinstitute_gatk_tools_walkers_genotyper_UnifiedGenotyper.php

java -jar GenomeAnalysisTK.jar

-R resources/Homo_sapiens_assembly18.fasta \

-T UnifiedGenotyper \

-I sample1.bam [-I sample2.bam ...] \

--dbsnp dbSNP.vcf \

-o snps.raw.vcf \

-stand_call_conf [50.0] \

-stand_emit_conf 10.0 \

-dcov [50 for 4x, 200 for >30x WGS or Whole exome] \

[-L targets.interval_list]

GATK Variant Quality Score Recalibrator

Creates a Gaussian mixture model by looking at the annotations values over a high quality subset of the input call set and then evaluate all input variants. http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/gatkdocs/org_broadinstitute_sting_gatk_walkers_variantrecalibration_VariantRecalibrator.html

java -Xmx4g -jar GenomeAnalysisTK.jar

-T VariantRecalibrator \

-R reference/human_g1k_v37.fasta \

-input NA12878.HiSeq.WGS.bwa.cleaned.raw.subset.b37.vcf \

-resource:hapmap,known=false,training=true,truth=true,prior=15.0 \

hapmap_3.3.b37.sites.vcf \

-resource:omni,known=false,training=true,truth=false,prior=12.0 \

1000G_omni2.5.b37.sites.vcf \

-resource:dbsnp,known=true,training=false,truth=false,prior=6.0 dbsnp_135.b37.vcf \

-an QD -an HaplotypeScore -an MQRankSum \

-an ReadPosRankSum -an FS -an MQ -an InbreedingCoeff \

-mode SNP \

-recalFile path/to/output.recal \

-tranchesFile path/to/output.tranches \

-rscriptFile path/to/output.plots.R

- HuVariome——————————————————————–http://huvariome.erasmusmc.nl/ The HuVariome project aims to determine rare and common genetic variation in a Northern European population (Benelux) based on whole genome sequencing results. Variations, their population frequencies and the functional impact are stored in the HuVariome Database. Users who provide samples for inclusion within the database are able to access the full content of the database, whilst guests can access the public set of genomes published by Complete Genomics.

Has a straightforward web interface.

- KGGSeq—————————————————http://statgenpro.psychiatry.hku.hk/limx/kggseq/ A biological Knowledge-based mining platform for Genomic and Genetic studies using Sequence data.

Usage

To prioritize variants based on the hg18 assembly for a rare Mendelian disease, need input files:

- a VCF file (rare.disease.hg18.vcf); and

-

a linkage pedigree file (rare.disease.ped.txt).

java -jar -Xms256m -Xmx1300m kggseq.jar examples/param.rare.disease.hg18.txt

- NEAT-genReads—————————————https://github.com/zstephens/neat-genreads.git NEAT-genReads is a fine-grained read simulator published in PLoS One 51. GenReads simulates real-looking data using models learned from specific datasets. Simulated reads can be whole genome, whole exome, specific targeted regions, or tumor/normal, with optional vcf and bam file outputs. Additionally, there are several supporting utilities for generating models used for simulation. Requires Python 2.7 and Numpy 1.9.1+.

Usage:

Simulate whole genome dataset with random variants inserted according to the default model. Generates paired-end reads, bam, and vcf output.

python genReads.py \

-r hg19.fa \

-R 101 \

-o /home/me/simulated_reads \

--bam \

--vcf \

--pe 300 30

Simulate a targeted region of a genome, e.g. exome, with -t. Generates paired-end reads, bam, and vcf output.

python genReads.py \

-r hg19.fa \

-R 101 \

-o /home/me/simulated_reads \

--bam \

--vcf \

--pe 300 30 \

-t hg19_exome.bed

- Picard MarkDuplicates—– https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/documentation/tooldocs/4.0.4.0/picard_sam_markduplicates_MarkDuplicates.php Examines aligned records in the supplied SAM or BAM file to locate duplicate molecules. All records are then written to the output file with the duplicate records flagged.

Usage

Starting with GATK4.0, all Picard tools are directly available from the GATK suit itself. This means that for older GATK releases, one would call a tool as below:

java -jar picard.jar MarkDuplicates [options] INPUT=File OUTPUT=File

Whereas for GATK4 releases, the same tool would be called as below:

gatk MarkDuplicates [options] --INPUT File --OUTPUT File

For a comprehensive list of options, see the utility’s documentation page listed above.

- Multiple databases can be used to annotate variants————–http://regulome.stanford.edu/ A database that annotates SNPs with known and predicted regulatory elements in the intergenic regions of the H. sapiens genome. Known and predicted regulatory DNA elements include regions of DNAase hypersensitivity, binding sites of transcription factors, and promoter regions that have been biochemically characterized to regulation transcription. Source of these data include public datasets from GEO, Chromatin States from the Roadmap Epigenome Consortium, the ENCODE project, and published literature.

Has a straightforward web interface.

- SAMtools———————————————————————-http://samtools.sourceforge.net/ ———————————————————————-http://www.htslib.org

SAM Tools provide various utilities for manipulating alignments in the SAM format, including sorting, merging, indexing and generating alignments in a per-position format.

SNP calling with mpileup http://samtools.sourceforge.net/mpileup.shtml

# Use Q to set base quality threshold:

samtools mpileup -Q 25 -ugf <reference.fasta> <file.bam> | \

bcftools view -bvcg - > accepted_hits.raw.bcf

# Convert bcf to vcf (vairant call format)

# and filter using varFilter (from vcfutils), if needed;

# use Q to set mapping quality; use d for minimum read depth:

bcftools view accepted_hits.raw.bcf | vcfutils.pl varFilter -d 5 -Q 20 > \

accepted_hits.raw.vcf

- SolexaQA++———————————————————————-http://solexaqa.sourceforge.net/ SolexaQA is a software package to calculate sequence quality statistics and create visual representations of data quality for Illumina’s second-generation sequencing technology (historically known as “Solexa”).

Usage

Running directly on Illumina FASTQ files:

./SolexaQA++ analysis FASTQ_input_files \

[-p|probcutoff 0.05] \

[-h|phredcutoff] \

[-v|variance] \

[-m|minmax] \

[-s|sample 10000] \

[-b|bwa] \

[-d|directory path] \

[-sanger -illumina -solexa]

- snpEff——————————————————————————http://snpeff.sourceforge.net/ Genetic variant annotation and effect prediction toolbox. Version 2.0.5 is is included in the GATK suit, but not newer versions. For human data, the recommendation is to use the GRCh37.64 database

Usage

# If you don't already have the database installed:

java -jar snpEff.jar download -v GRCh37.66

# Annotate the file:

# Use appropriate i) organism and ii) annotation (eg. UCSC, RefSeq, Ensembl)

# E.g. mouse: mm37 (UCSC/RefSeq), mm37.61 (Ensembl)

# Human: hg37 (UCSC/RefSeq), hg37.61 (Ensembl)

# Output is created in several files:

# an html summary file and text files with detailed information.

java -jar snpEff.jar -vcf4 GRCh37.75 accepted_hits.raw.filtered.vcf >accepted_hits.raw.filtered.snpEff

- SnpSift————————————————————-http://snpeff.sourceforge.net/SnpSift.html Helps filter and manipulate annotated files. Included in GATK.

Once your genomic variants have been annotated, you need to filter them out in order to find the “interesting / relevant variants”. Given the large data files, this is not a trivial task (e.g. you cannot load all the variants into XLS spreasheet). SnpSift helps to perform this VCF file manipulation and filtering required at this stage in data processing pipelines.

Usage

To filter out samples with quality less than 30:

cat variants.vcf | java -jar SnpSift.jar filter " ( QUAL >= 30 )" > filtered.vcf

To do the same but keep InDels that have quality 20 or more:

cat variants.vcf | java -jar SnpSift.jar filter \

"(( exists INDEL ) & (QUAL >= 20)) | (QUAL >= 30 )" \

> filtered.vcf

The Variant Annotation, Analysis and Search Tool) is a probabilistic search tool for identifying damaged genes and their disease-causing variants in personal genome sequences. VAAST builds upon existing amino acid substitution (AAS) and aggregative approaches to variant prioritization, combining elements of both into a single unified likelihood-framework that allows users to identify damaged genes and deleterious variants with greater accuracy, and in an easy-to-use fashion. VAAST can score both coding and non-coding variants, evaluating the cumulative impact of both types of variants simultaneously. VAAST can identify rare variants causing rare genetic diseases, and it can also use both rare and common variants to identify genes responsible for common diseases. VAAST thus has a much greater scope of use than any other existing methodology.

It has outstanding quickstart quide: http://www.yandell-lab.org/software/VAAST/VAAST_Quick-Start-Guide.pdf

Usage

The set of genomes being analyzed for disease causing features (cases) are referred to as the target genomes. The set of healthy genomes (controls) that the target genomes are being compared to are referred to as the background genomes. The basic inputs to VAAST consist of:

- A set of target (case) variant files in either VCF or GVF format.

- A set of background (control) variant files in either VCF or GVF format.

- A set features to be scored, usually genes; this file should be in gff3 format.

-

A multi-fasta file of the reference genome

../bin/VAT -f data/easy-hg18-chr16.gff3 \ -a data/hg18-chr16.fasta data/miller-1.gvf > data/miller-1.vat.gvf

VCF can be easily converted to GVF using the vaast_converter script, included with the distribution: VAAST/bin/vaast_tools/vaast_converter.

Bibliography

-

Heldenbrand, J. R. et al. Performance benchmarking of GATK3.8 and GATK4. BioRxiv (2018). doi:10.1101/348565 ↩ ↩2

-

Laurie, S. et al. From Wet-Lab to Variations: Concordance and Speed of Bioinformatics Pipelines for Whole Genome and Whole Exome Sequencing. Hum. Mutat. 37, 1263–1271 (2016). ↩

-

Hwang, S., Kim, E., Lee, I. & Marcotte, E. M. Systematic comparison of variant calling pipelines using gold standard personal exome variants. Sci. Rep. 5, 17875 (2015). ↩

-

GATK Dictionary. at https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/documentation/topic?name=dictionary ↩

-

Myllykangas, S., Buenrostro, J. & Ji, H. P. Overview of sequencing technology platforms. InBioinformatics for High Throughput Sequencing 11–25 (Springer New York, 2012). doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0782-9_2 ↩

-

Schiemer, J. Illumina TruSeq DNA Adapters De-Mystifie available from http://tucf-genomics.tufts.edu/documents/protocols/TUCF_Understanding_Illumina_TruSeq_Adapters.pdf . ↩

-

Goodwin, S., McPherson, J. D. & McCombie, W. R. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 333–351 (2016). ↩

-

Head, S. R. et al. Library construction for next-generation sequencing: overviews and challenges. BioTechniques 56, 61–4, 66, 68, passim (2014). ↩

-

Regier, A. A. et al. Functional equivalence of genome sequencing analysis pipelines enables harmonized variant calling across human genetics projects. BioRxiv (2018). doi:10.1101/269316 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9

-

Pabinger, S. et al. A survey of tools for variant analysis of next-generation genome sequencing data. Brief. Bioinformatics 15, 256–278 (2014). ↩ ↩2

-

Nielsen, R., Paul, J. S., Albrechtsen, A. & Song, Y. S. Genotype and SNP calling from next-generation sequencing data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 443–451 (2011). ↩

-

broadinstitute/gatk: Official code repository for GATK versions 4 and up. at https://github.com/broadinstitute/gatk ↩

-

Cock, P. J. A., Fields, C. J., Goto, N., Heuer, M. L. & Rice, P. M. The Sanger FASTQ file format for sequences with quality scores, and the Solexa/Illumina FASTQ variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 1767–1771 (2010). ↩

-

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014). ↩ ↩2

-

Dodt, M., Roehr, J. T., Ahmed, R. & Dieterich, C. FLEXBAR-Flexible Barcode and Adapter Processing for Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms. Biology (Basel) 1, 895–905 (2012). ↩

-

Tools to remove adapter sequences from next-generation sequencing data, Genomics Gateway. at http://bioscholar.com/genomics/tools-remove-adapter-sequences-next-generation-sequencing-data/ ↩

-

Adapter trimming software tools, WGS analysis - OMICtools. at https://omictools.com/adapter-trimming-category ↩

-

Del Fabbro, C., Scalabrin, S., Morgante, M. & Giorgi, F. M. An extensive evaluation of read trimming effects on Illumina NGS data analysis. PLoS ONE 8, e85024 (2013). ↩

-

Babraham Bioinformatics - FastQC A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. at http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ ↩

-

Schmieder, R. & Edwards, R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 27, 863–864 (2011). ↩

-

Cox, M. P., Peterson, D. A. & Biggs, P. J. SolexaQA: At-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 485 (2010). ↩

-

GATK Doc Article #1213. at https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/documentation/article.php?id=1213 ↩

-

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. (2013). ↩ ↩2

-

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). ↩

-

Li, H. & Homer, N. A survey of sequence alignment algorithms for next-generation sequencing. Brief. Bioinformatics 11, 473–483 (2010). ↩

-

Thankaswamy-Kosalai, S., Sen, P. & Nookaew, I. Evaluation and assessment of read-mapping by multiple next-generation sequencing aligners based on genome-wide characteristics. Genomics 109, 186–191 (2017). ↩

-

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). ↩

-

How PCR duplicates arise in next-generation sequencing. at http://www.cureffi.org/2012/12/11/how-pcr-duplicates-arise-in-next-generation-sequencing/ ↩

-

Faust, G. G. & Hall, I. M. SAMBLASTER: fast duplicate marking and structural variant read extraction. Bioinformatics 30, 2503–2505 (2014). ↩

-

Tarasov, A., Vilella, A. J., Cuppen, E., Nijman, I. J. & Prins, P. Sambamba: fast processing of NGS alignment formats. Bioinformatics 31, 2032–2034 (2015). ↩

-

NOVOCRAFT TECHNOLOGIES SDN BHD. Novocraft. NOVOCRAFT TECHNOLOGIES SDN BHD at http://www.novocraft.com/ ↩

-

Picard Tools - By Broad Institute. at https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ ↩

-

DePristo, M. A. et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 43, 491–498 (2011). ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Albers, C. A. et al. Dindel: accurate indel calls from short-read data. Genome Res. 21, 961–973 (2011). ↩

-

Homer, N. & Nelson, S. F. Improved variant discovery through local re-alignment of short-read next-generation sequencing data using SRMA. Genome Biol. 11, R99 (2010). ↩

-

Van der Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 11, 11.10.1-11.10.33 (2013). ↩ ↩2

-

Rimmer, A. et al. Integrating mapping-, assembly- and haplotype-based approaches for calling variants in clinical sequencing applications. Nat. Genet. 46, 912–918 (2014). ↩

-

Garrison, E. & Marth, G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. arXiv (2012). ↩

-

Poplin, R. et al. Scaling accurate genetic variant discovery to tens of thousands of samples. BioRxiv (2017). ↩ ↩2

-

Ebbert, M. T. W. et al. Evaluating the necessity of PCR duplicate removal from next-generation sequencing data and a comparison of approaches. BMC Bioinformatics 17 Suppl 7, 239 (2016). ↩

-

Olson, N. D. et al. Best practices for evaluating single nucleotide variant calling methods for microbial genomics. Front. Genet. 6, 235 (2015). ↩

-

Cabanski, C. R. et al. ReQON: a Bioconductor package for recalibrating quality scores from next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 221 (2012). ↩

-

Bansal, V. A statistical method for the detection of variants from next-generation resequencing of DNA pools. Bioinformatics 26, i318-24 (2010). ↩

-

Cibulskis, K. et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 213–219 (2013). ↩

-

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011). ↩

-

Li, H. Toward better understanding of artifacts in variant calling from high-coverage samples. Bioinformatics 30, 2843–2851 (2014). ↩

-

hail-is/hail: Scalable genomic data analysis. at https://github.com/hail-is/hail ↩

-

Paila, U., Chapman, B. A., Kirchner, R. & Quinlan, A. R. GEMINI: integrative exploration of genetic variation and genome annotations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1003153 (2013). ↩

-

Peng, G. et al. Rare variant detection using family-based sequencing analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 3985–3990 (2013). ↩

-

Boyle, A. P. et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 22, 1790–1797 (2012). ↩

-

Stephens, Z. D. et al. Simulating Next-Generation Sequencing Datasets from Empirical Mutation and Sequencing Models. PLoS ONE 11, e0167047 (2016). ↩ ↩2

-

What’s in the resource bundle and how can I get it? — GATK-Forum. at https://gatkforums.broadinstitute.org/gatk/discussion/1213/whats-in-the-resource-bundle-and-how-can-i-get-it ↩

-

Afgan, E. et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W537–W544 (2018). ↩

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.