Introduction

The genes encoding the RNA component of the small subunit of ribosomes, commonly known as the 16S rRNA in bacteria and archaea, are among the most conserved across all kingdoms of life. Nevertheless, they contain regions that are less evolutionarily constrained and whose sequences are indicative of their phylogeny. Amplification of these genomic regions by PCR from an environmental sample and subsequent sequencing of a sufficiently large number of individual amplicons enables the analysis of the diversity of clades in the sample and a rough estimate of their relative abundance. The analytical process is known as “16S rDNA diversity analysis”, and is the focus of the present SOP.

The SOP describes the essential steps for processing 16S rRNA gene sequences. The procedure and tools are only recommendations and it is up to the user to evaluate what works best for their needs.

Glossary of terms and jargon

- 16S rRNA gene

- The gene that is responsible for the coding of the 16S ribosomal RNA. The gene is used in constructing phylogenies.

- Barcodes

- Short nucleotide sequences added onto the ends of the DNA fragments that are to be sequenced. It allows for indexing of samples, so multiple DNA libraries can be mixed together into one sequencing lane.

- Variable region

- 16S rRNA gene sequences contain hypervariable regions that can provide clade-specific signature sequences useful for bacterial identification.

- Demultiplex

- This is a process of binning reads based on barcodes, primarily used to split them amongst samples.

- Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU)

- An operational taxonomic unit is an operational definition of a species or group of species often used when only DNA sequence data is available.

- Rarefaction analysis

- Rarefaction is a process used to estimate the true diversity of a sample by extracting random subsets of sequences. The analysis estimates diversity from subsets of different sizes and extrapolates the resulting rarefaction curve to an infinite number of sequences. Rarefaction is also used to determine whether the sequencing depth achieved (number of reads per sample) is sufficient to capture the diversity within a sample. A plot is generated showing increase in number of species (or other diversity metrics) as the number of sequence reads increase. A curve that is reaching asymptote indicates that no further diversity would be expected if sequencing depth was increased.

- Phred quality score or Q score

- Measure of sequencing accuracy. Logarithmically related to the probability that a base is called incorrectly by a sequencer. Example: a Phred score of 30 (Q30) means that the probability of an incorrect call for that base is 1 in 1000 and the base call accuracy is 99.9%. The base call accuracy for a base with Q10 is 90%, Q20 is 99%, Q30 is 99.9%, Q40 is 99.99%, and Q50 = 99.999%.

- Adapter

- Platform specific nucleotide sequence added to the ends of DNA molecule to facilitate sequencing e.g. in Illumina the adapter facilitates binding to the complementary target sequences mobilised on the flow cell.

- Chimera

- PCR artefact. Chimeras are potentially formed during PCR when incompletely extended DNA fragments from different templates anneal due to closely related sequences generating recombinants between starting templates. Chimeras can greatly impact estimates of diversity (generally overestimate).

- Alpha diversity

- Diversity within a single sample. Diversity can be characterised using the number of different species (richness), the abundance of each species (evenness), with indices that combine richness and evenness, and with divergence-based methods (phylogenetic diversity).

- Beta diversity

- Comparison of diversity between samples.

- Unifrac

- Beta diversity distance metric based on the phylogenetic distance between the members of communities/samples. Unifrac captures the total amount of evolution that is unique to each sample.

- ASV

- Amplicon sequence variance

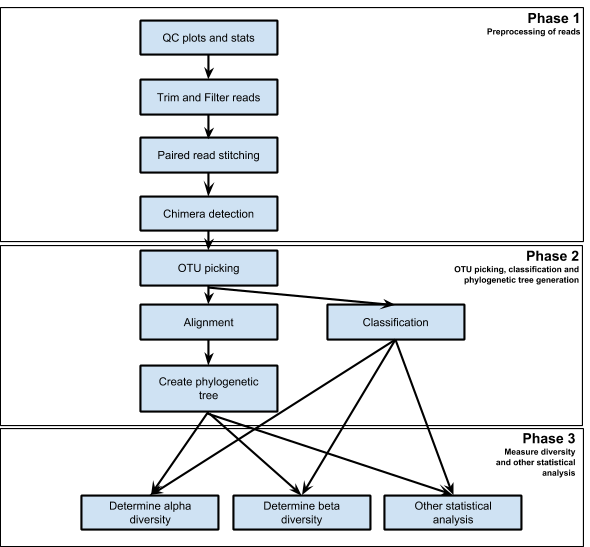

Schematic workflow of the analysis

|

|---|

| Figure 1. Steps in 16s Analysis Workflow |

Phase 1: Preprocessing of reads

It is essential to preprocess raw reads before subjecting them for downstream analysis. The preprocessing includes the removal of low quality bases, ambiguous bases and adapter sequences, the stitching together of paired reads, and the detection of chimeric reads. Sequencing errors, reads with ambiguous bases and chimeras can all cause the appearance of spurious OTUs if they are not removed.

Input: raw reads (multiplexed or demultiplexed)

Output: high quality reads ready for OTU picking

QC plots and stats

The first step in the data preprocessing is to check the quality of bases in all the reads. Once we understand the quality spectrum of the reads, we can decide on the parameters for trimming low quality bases. If the raw reads are not demultiplexed, demultiplexing should be performed before proceeding to the next step. Illumina’s CASAVA or QIIME tools can perform the demultiplexing task.

Software: FASTQC, MutliQC, PRINSEQ, SolexaQA

Trim and Filter reads

Data received from sequencing facilities might still contain sequencing artefacts and would therefor need to be removed or reads need to be filtered. For example at the 3’ end of reads there are often adaptor sequences left from library preparation. These adaptor bases need to be removed, and low quality bases need to be trimmed off. Any of the indicated programs can be used for this. Bokulich et al. 2013 1 recommend a minimum phred quality score of 3 to trim low quality bases at the ends of the reads. Jeraldo et al. 2014 (in review) recommend trimming the 3’ end of the reads with a moving average score of 15, with a window size of 4 bases and to removal of any reads shorter than 75% of the original read length. It is also recommended that reads containing ambiguous bases (N) be discarded.

Software: Trimmomatic, PRINSEQ, SolexaQA

Paired read stitching

When the combined length of reads sequenced from both ends of DNA fragments is longer than the size of the fragment, there is an overlap between the paired reads. The read pairs can be stitched together based on the overlap information, thus generating a single sequence. During the read stitching process, higher quality bases can be selected thus improving the quality of stitched reads. PANDASeq does not do well when the overlap is almost the entire read. PEAR works well for all lengths of overlaps between the paired reads.

Software: PEAR, PANDASeq, FLASH, UPARSE merge

Chimera detection

Chimeras are artifacts of PCR. These are formed during PCR cycles by the joining of two or more different parent DNA templates. If these chimeras are not removed they may be recognized as novel sequences during the alignment process and therefore mislead interpretation. At present there are no tools that can remove chimeras completely without throwing away non-chimeric sequences. Of the various tools available, UCHIME was found to perform better than ChimeraSlayer, which was the best program to detect chimeras before UCHIME was developed2. To remove chimeras from 454 sequences Perseus can also be used3.

Software: UCHIME, ChimeraSlayer, Perseus

Phase 2: OTU picking, classification and phylogenetic tree generation

During this phase reads are processed so that comparisons between samples can be made. The first step is to cluster reads based on similarity into OTUs and to select a representative sequence for each OTU. Each OTU is then classified by comparison to a reference database and a phylogeny inference is made based on sequence alignment and the construction of a phylogenetic tree.

Input: high quality reads

Output: OTUs, representative sequences, OTU table with classification and abundance of each OTU, heatmap, sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree

OTU picking

OTU picking is the clustering of the preprocessed reads into OTUs. The clusters are formed based on sequence identity. The identity threshold can be defined by the user. Sequences that are more than 97% identical are conventionally assumed to be derived from the same bacterial species/OTU. Other identity percentages can be used, depending on the granularity of the desired clusters and the known divergence in 16S sequences of the OTUs of interest. Three approaches for OTU picking exist. 1) de novo OTU picking groups sequences based on levels of pairwise sequence identity; 2) closed reference OTU picking aligns and groups sequences relative to a reference database, and sequences that are not >97% identical to a known reference are discarded 3) open-reference OTU picking starts with alignment to a reference database, but if the read does not match a known sequence it is not discarded but sent for de novo OTU picking. After the sequences have been clustered into OTUs and counted to estimate OTU abundance, a representative sequence is picked for each OTU. Each OTU is therefore represented by a single sequence and this will speed up downstream analysis. There are multiple choices to select a representative sequence. It can be the first sequence, the longest sequence, the seed sequence used in OTU picking, the most abundant sequence or a random sequence.

Software: UPARSE, QIIME

ASV prediction

Exact ASV prediction prove to be a good alternative to OTU picking (Callahan, B. J. et al 2016 4). The process infers sample sequences exactly and resolve differences to as little as one nucleotide sequences. This approach allows for more accurate taxonomic classification and has additional benefits such as the reuse of previously processed sample ASVs in future projects (Callahan, B. J. et al 2017 5). DADA2 is an R package that contains a complete pipeline read processing, ASV prediction and classification. QIIME2 has a DADA2 interface though there might be limitations on what settings can be configured when running through QIIME2 and not natively through R.

Software: DADA2, QIIME2

Classification

Here a taxonomic identity is assigned to each representative sequence. The taxonomies are pulled from a reference set. There are three main reference databases with aligned, validated and annotated 16S rRNA genes: GreenGenes, Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) and Silva. Each of these databases has strengths and weaknesses that need to be taken into consideration, and all are in common use. Several methods for assigning taxonomy against these reference databases exist, including UCLUST, the RDP classifier and RTAX.

Databases: SILVA, GreenGenes, RDP

Software: UCLUST, the RDP classifier, RTAX

Alignment

To understand the evolutionary relationships between the sequences in the sample and to perform a diversity analysis, it is necessary to generate a phylogenetic tree of the OTUs. The first step in generating the tree is to generate a multiple alignment of the representative OTU sequences. PyNAST aligns the sequences to a template alignment of reference 16S sequences. Infernal makes use of a Hidden Markov Model that also incorporates secondary structure information.

Software: PyNAST, INFERNAL

Create phylogenetic tree

The phylogenetic tree represents the relationship between the sequences in terms of the evolutionary distance from a common ancestor. In downstream analysis this tree is used for example in calculating the UniFrac distances.

Software: FastTree

An alternate option to most of the steps mentioned in phase 1 and phase 2 is to run IM-TORNADO (Jeraldo et al. 2014 in review). IM-TORNADO is an integrated pipeline that takes demultiplexed reads and trims low quality bases, does paired read stitching, removes chimeras and generates OTU table, phylogenetic tree and assigns taxonomy. Unique feature of IM-TORNADO is that it can analyze paired reads that do not overlap. Non-overlapping paired reads are typically generated from non-overlapping variable regions of 16S rRNA. Such studies try to utilize information in two variable regions instead of one variable region as in any standard 16S rRNA study to define OTUs.

Phase 3: Measure diversity and other statistical analysis

OTU information (number of OTUs, abundance of OTUs) and the phylogenetic tree generated from the phase 2 is utilized to estimate diversity within and between samples. Additional statistical analysis to test the significance of the diversities can also be done.

Input: classified OTU table with abundance, phylogenetic tree and sample metadata

Output: alpha and beta diversity metrics, distance matrix, results from statistical tests, rarefaction plots, PCoA plots, heatmaps

Determine alpha diversity

Alpha diversity is a measure of diversity within a sample. It gives an indication of richness and/or evenness of species present in a sample. The accuracy of the measured diversity is mainly affected by the sequencing depth (number of reads per sample). Sequencing depth must be high enough to capture the true diversity within a sample. Samples with higher number of reads would show higher diversity than samples with lower number of reads. Rarefaction analysis is therefore required to understand the actual diversity within a sample and to determine if your sequencing effort is sufficient and if the total diversity within the sample has been captured. Mothur as well as QIIME have tools to generate multiple rarefactions and then measure alpha diversity on the rarefied OTU tables. Several popular alpha diversity measures are available both in Mothur and QIIME: Shannon index, chao1, observed species, and phylogenetic diversity whole tree.

Software: mothur, QIIME

Determine beta diversity

Beta diversity is a measure of diversity between samples. One of the most commonly used metrics is the Unifrac distance that compares samples using phylogenetic information. An all-by all or pairwise matrix of the beta diversity metrics between all the samples in the study is generated and can be visualized in different ways such as a tree, graph, network etc. Mothur and QIIME have several tools to generate distance metrics, phylogenetic trees and PCoA plots.

Software: UNIFRAC for distance metrics, mothur, QIIME

Other statistical analysis

Additional statistical tests between samples or groups of samples can be done in QIIME. For alpha diversity a parametric or non-parametric t-test can be performed on a rarefied number of sequences. For beta diversity the Mantel, partial Mantel and Mantel correlogram matrix correlation can be used to compare distance matrices. Multivariate analyses are also available for testing significance between the distance matrix and other factors. The statistical methods available are: adonis, ANOSIM, BEST, Moran’s I, MRPP, PERMANOVA, PERMDISP, and db-RDA. Native methods in R and other R packages such as phyloseq and ade4 can also be considered for these types of analyses.

Software: QIIME, R packages (phyloseq, ade4)

Additional notes

In the SOP we refer both to QIIME and QIIME2. QIIME2 is more of a platform / command line interface than the original QIIME that contained a set of Python wrapper scripts. The QIIME developers suggest migrating to QIIME2.

vsearch is an open source alternative to usearch and our testing showed that it performs equally well on the H3ABioNet test dataset. There is no 64 bit memory limitation when using vsearch.

Appendices

Tools referred to in SOP

- FASTQC - http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc

- MultiQC - https://multiqc.info/

- PRINSEQ - http://edwards.sdsu.edu/cgi-bin/prinseq/prinseq.cgi

- SolexaQA - http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/11/485

- PEAR - http://bioinformatics.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2013/10/18/bioinformatics.btt593.full.pdf

- PANDASeq - http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/13/31

- FLASH - http://bioinformatics.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/09/07/bioinformatics.btr507.full.pdf

- UCHIME - http://drive5.com/usearch/manual/uchime_algo.html

- ChimeraSlayer - http://nebc.nox.ac.uk/bioinformatics/docs/chimeraslayer.html

- Perseus - http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/12/38/

- UPARSE - http://www.drive5.com/uparse/

- vsearch = https://github.com/torognes/vsearch

- UCLUST - http://www.drive5.com/uclust/downloads1_2_22q.html

- RDP classifier - http://sourceforge.net/projects/rdp-classifier/files/rdp-classifier/

- RTAX - https://github.com/davidsoergel/rtax

- PyNAST - http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19914921

- INFERNAL - http://infernal.janelia.org/

- FastTree - http://www.microbesonline.org/fasttree/

- IM-TORNADO - http://sourceforge.net/projects/imtornado/

- Mothur - http://www.mothur.org/

- QIIME - http://qiime.org/

- QIIME2 - https://qiime2.org/

- UNIFRAC - http://bmf.colorado.edu/unifrac/

- R packages

Databases referred to in SOP

- SILVA - http://www.arb-silva.de/

- Greengenes - http://greengenes.lbl.gov/

- RDP classifier - http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/

H3ABioNet Assessment exercises

Practice dataset

The input datasets and metadata can be accessed here.

Input data assessment Questions

- Were the number, length and quality of the reads obtained in line with what would be expected for the sequencing platform used?

- Was the input dataset of sufficiently good quality to perform the analysis?

- How did the reads’ quality and GC content affect the way analysis was run?

Operational assessment questions

- At each step of the workflow, describe which software was used and why:

- Was the choice affected by the nature and/or quality of the reads?

- Was the choice made due to the time and cost of the analysis?

- What are the accuracy and performance considerations for the chosen piece of software?

- For each software, describe which input parameters were chosen, and why:

- Was the choice affected by the nature and/or quality of the reads?

- Did the available hardware play a role in the parameter choice?

- How did the purpose of the study affect the parameter choice?

- For each step of the workflow, how do you know that it completed successfully and that the results are usable for the next step?

Runtime analysis

This is useful information for making predictions for the clients and collaborators

- How much time and disk space did each step of the workflow take?

- How did the underlying hardware perform? Was it possible to do other things, or run other analyses on the same computer at the same time?

Analysis of the results

- What percentage of the reads were removed during the quality trimming step? Did all samples have similar number of reads after the preprocessing of reads steps? What was the median, maximum and minimum read count per sample? How many reads were discarded due to ambiguous bases?

- What percentage of reads could not be stitched? Were unstitched reads retained or discarded?

- How many chimeras were detected?

- How does the trimming or filtering strategy affect the the number of OTUs picked and the classification and phylogenetic analysis of the OTUs?

- How does the % similarity threshold used during OTU picking affect the number of OTUs identified and the classification and phylogenetic analysis of the OTUs?

- How many OTUs were picked? What percentage of the OTUs could be classified to the genus and species level? What percentage of OTUs could only be assigned to taxonomic ranks higher than genus? What is the confidence threshold for the classifications?

- Does the use of a different 16S rRNA database for classification affect the results (e.g. were a lesser or greater number of OTUs classified to lower taxonomic ranks (genus, species))? Were any OTUs classified differently?

- Did the samples have enough sequence depth to capture the diversity? Did the rarefaction curve flatten? Should any samples be excluded because of low read count?

- Were there any differences in the alpha diversity between the samples in the different metadata categories (e.g. higher phylogenetic diversity in treatment 1 vs. treatment 2)?

- When groups of samples were compared (e.g. treatment 1 vs. treatment 2) based on distance metrics, such as unifrac, was there any particular clustering pattern observed?

- Were any of the OTUs significantly correlated to any of the treatments or other metadata?

Bibliography

-

Bokulich, Nicholas A., et al. “Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing.” Nature methods 10.1 (2013): 57. ↩

-

Edgar, Robert C., et al. “UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection.” Bioinformatics 27.16 (2011): 2194-2200. ↩

-

Quince, Christopher, et al. “Accurate determination of microbial diversity from 454 pyrosequencing data.” Nature methods 6.9 (2009): 639. ↩

-

Callahan, B. J., et al. “DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data.” Nature methods, 13.7 (2016), 581-3. ↩

-

Callahan, B. J., et al. “Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis.” The ISME journal, 11(12), 2639-2643. ↩

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.