Introduction

This document outlines the essential steps in the process of analyzing gene expression data using RNA sequencing (mRNA, specifically), and recommends commonly used tools and techniques for this purpose. It is assumed in this document that the experimental design is simple and that differential expression is being assessed between 2 experimental conditions, i.e. a simple 1:1 comparison, with some information about analyzing data from complex experimental designs. The focus of the SOP is on single-end strand-specific reads, however special measures to be taken for analysis of paired-end data are also briefly discussed. The recommended coverage for RNA-Seq on human samples is 30-50 million reads (single-end), with a minimum of three replicates per condition, preferably more if one can budget accordingly. Preference is also generally given for a higher number of replicates with a lower per-sample sequence yield (15-20 million reads) if there is a tradeoff between the number of reads per sample and the total number of replicates.

The procedures outlined below are recommendations to the H3ABioNet groups planning to do differential gene expression analysis on human RNA-Seq data, and are not meant to be prescriptive. Our goal is to help the groups set up their procedures and workflows, and to provide an overview of the main steps involved and the tools that can be used to implement them.

Glossary of associated terms and jargon

- FASTQ format & quality scores

- FASTQ format is the standard format of raw sequence data. Quality scores assigned in the FASTQ files represent the probability that a certain base was called incorrectly. These scores are encoded in various ways and it is important to know the type of encoding for a given FASTQ file.

- Single-end vs paired-end, read vs fragment

- DNA fragments can be sequenced from one end or both ends, single-end (SE) or paired-end (PE) respectively. During data processing PE data will often be represented as fragments consisting of 2 reads, instead of 2 separate reads.

- Strandedness

- During library prep RNA can be processed into cDNA such the strand information is maintained. This is important in regions where there are overlapping genes on the two DNA strands

- TPM, RPKM, FPKM, CPM

- Acronyms that stand for:

- TPM: Transcripts Per Million

- RPKM - Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads (for SE data)

- FPKM - Fragments Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads (for PE data)

- CPM - Counts Per Million

- TMM

- This is a type of normalization and is an acronym for “Trimmed Mean of Ms”1.

Procedural steps

This protocol paper 2 was a very good resource for understanding the procedural steps involved in any RNA-Seq analysis. The datasets they use in that paper are freely available, but the source of RNA was the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster, and not Human tissue. In addition, they exclusively use the “tuxedo” suite developed in their group.

Several papers are now available that describe the steps in greater detail for preparing and analyzing RNA-Seq data, including using more recent statistical tools:

In addition, newer alignment-free methods have also been published and are increasingly being used in analysis (we include a second protocol detailing the use of these):

The sections below detail those protocols and suggest tools.

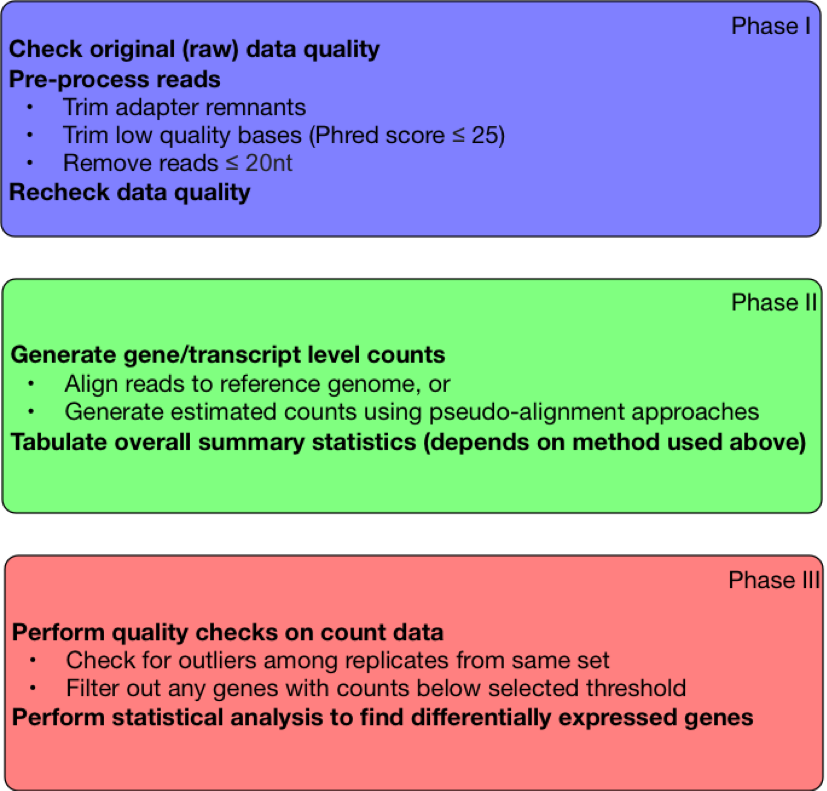

|

|---|

| Figure 1. Steps in RNA-Seq Workflow |

Phase 1: Preprocessing of the raw reads

The following steps prepare reads for analysis and should be always performed prior to alignment.

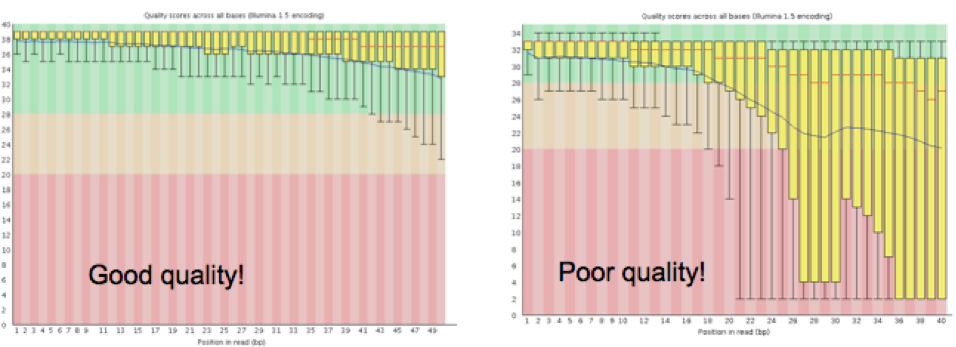

Step 1.1: Quality check

The overall quality of the sequence information received from the sequencing center will determine how the quality trimming should be set up in Step 1.2. Tools like FastQC8 will enable the collection of this information. Sequencing facilities usually produce read files in FASTQ format, which contain a base sequence and a quality score for each base in a read. FastQC measures several metrics associated with the raw sequence data in the FASTQ file, including read length, average quality score at each sequenced base, GC content, presence of any overrepresented sequences (k-mers), and so on. The key metric to watch for is the graph representing the average quality scores (see Figure 2), and the range of scores at each base along the length of the reads (reads are usually the same length at this time, and this length is the X-axis, the Y-axis has the quality scores). Note that for large projects, you may collate all of the FastQC reports by using a tool like MultiQC9. MultiQC will generate an html file that visually summarizes these metrics across all samples, as well as provide tab-delimited files containing all the FastQC stats.

|

|---|

| Figure 2. Graphs generated by FastQC detailing the average quality scores across all reads at each base. |

Step 1.2: Adaptor and Quality trimming + Removal of very short reads

In this step we deal with 3 major preprocessing steps that clean up the data and reduce noise in the overall analysis.

-

Adaptors (glossary term) are artificial pieces of DNA introduced prior to sequencing to ensure that the DNA fragment being sequenced attaches to the sequencing flow cell. Usually these adaptors get sequenced, and have already been removed from the reads. But sometimes bits of adaptors are left behind, anywhere from 90% to 20% of the adaptor length. These need to be removed from the reads. The adaptor sequence for this step will have to be obtained from the same source as the sequence data.

-

Frequently, the quality of bases sequenced tends to drop off toward one end of the read. A low quality base call means that the nucleotide assigned has a higher probability of being incorrect (see this link for a more in-depth overview of quality scores). It is best to trim off any low quality bases at the ends of reads to ensure the best alignment to the reference. Usually a quality score of <25 is considered as a “poor” quality score.

-

Once the adaptor remnants and low quality ends have been trimmed, some reads may end up being very short (i.e. <20 bases). These short reads are likely to align to multiple (wrong) locations on the reference, introducing noise. Hence any reads that are shorter than a predetermined cutoff (e.g. 20) need to be removed

One tool that deals with all of these issues at once is Trimmomatic10, though there are various alternatives that can perform these 3 clean up steps either combined or one after the other; these are listed below. For data that are paired ended, it is very important to perform the trimming for both read1 and read2 simultaneously. This is because all downstream applications expect paired information, and if one of the 2 reads is lost because it is too short, then the other read becomes unpaired (orphaned) and cannot be used properly for most applications. Trimmomatic has 2 modes, one for single end data (SE) and another one for paired end data (PE). If using paired end reads, please be sure to use the PE mode with both read1 and read2 FASTQ files for the same run.

Alternative Tools:

-

For adaptor trimming: Trim_Galore11, BBMap12, Flexbar13 and one of the many tools listed here.

-

For trimming low quality bases from the ends of reads: Trim_Galore11, BBMap12, FASTX-Toolkit (

fastq_quality_filter)14,PrinSeq15,SolexaQA16. -

For removing very short reads:

PrinSeq15, Trim_Galore11

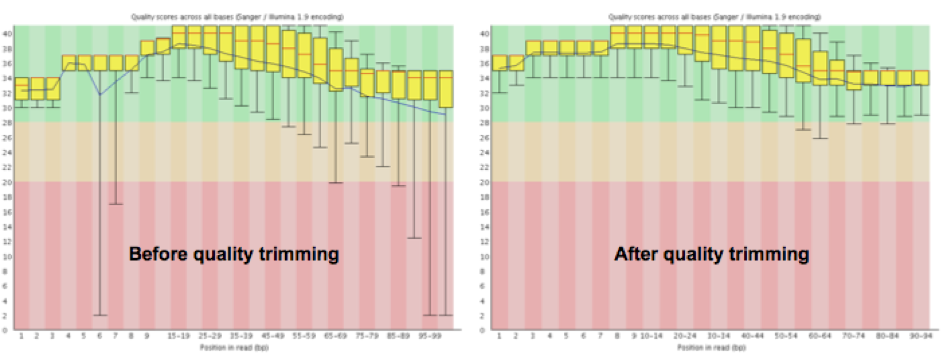

Step 1.3: Quality recheck

Once the trimming step is complete, it is always good practice to make sure that your dataset looks better by rerunning FastQC on the trimmed data. The metrics to compare between trimmed and raw fastq data, in the context of the tool FastQC are listed below:

- Sequence length and Sequence length distribution (the minimum will be lower in trimmed data)

- The quality score graph (majority of the bases will have a minimum quality value at or above 30, see Figure 3 below)

- Per base sequence content (should remain about the same)

|

|---|

| Figure 3. Graphs generated by FastQC detailing the change in average base quality across all reads after trimming in an example dataset. |

Phase 2: Determining how many read counts are associated with known genes

Step 2.1: Generation of gene/transcript-level counts

Below are two protocols for generation of gene- and transcript-level counts. Protocol 1 focuses on the classical alignment-based approach, whereas Protocol 2 uses recent advances in accelerated kmer-based ‘pseudo-alignment’17, 18, 19 approaches for assigning reads to transcripts, which has some distinct advantages to alignment methods but rely on having a comprehensive and reliably annotated transcriptome.

Protocol 1: Alignment-based approach

Once the data are cleaned up, the next step is alignment to the reference genome. There are various tools available for this step, but it is important that the alignment tool chosen here is a “splice-aware” tool. That means that the tool should have the capability to align reads that contain exonic sequences from 2 exons on either side of one intron (also called intron-spanning reads). STAR20, HISAT221, GSNAP22, SOAPSplice23 are some of the many splice-aware aligners available. Note that TopHat used to be a very commonly-used tool from the Tuxedo suite, however this software is no longer supported and has been superseded by HISAT2 (recommended for human data).

When performing alignments it is imperative to set up the parameters properly to ensure the best alignment. Irrespective of the aligner used, it needs the following information:

- Are the data made up of single-end reads or paired-end reads?

- Are the data stranded, if so, was the standard dUTP method employed (STAR can detect this automatically)?

The other information that should be provided when setting up the alignment is the gene annotation information, a GTF or GFF3 file that contains the information about the location of all the genes in the context of the reference genome (a FASTA file). It is very important to pick the gene annotation file that corresponds to the reference genome, i.e. the same version number and from the same source (Ensembl, UCSC or NCBI).

Note, that most all aligners require an index file to be created from the reference genome (a FASTA file). This helps speed up alignment drastically. For STAR, this index can be created using the “genomeGenerate” mode with or without an annotation file.

Once the alignment is complete, the final result will be a file in SAM or BAM format. For a STAR run, the main alignment output will end in “Aligned.out.sam” by default, but it may also be returned in a sorted or unsorted BAM file. In addition, there are two log files that are returned from STAR that report the progress of the run and save a summary of the final results. There is also a splice junctions (SJ) file that details high confidence splice junctions.

Once the alignment is completed, the first step is to check how many reads aligned to the genome. For STAR, all of these details can be found in the “Log.final.out” file. For RNA-Seq on Human samples, for good quality data, about 70 - 90% of the reads should match somewhere on the genome. If the data in question are of good quality but < 60 % of the reads are mapping to the genome, it is worth evaluating the parameters, and testing unmapped reads for presence of potential contaminants.

Protocol 2: Estimated counts using graph-based or similar approaches

A more recent alternative to alignment-based methods both dramatically increases the speed of the analysis and resolves some of issues that make analysis of transcripts or gene families problematic using alignment-based approaches. These methods use an alternative approach that performs essentially a very lightweight ‘alignment’ that speeds up analysis, sometimes by orders of magnitude. These approaches also generate (as output) estimated counts that can be imported into standard R-based workflows, thus combining the initial two steps in the alignment-based approach above.

The speedups are based on the tool being used and are accomplished in slightly different ways, such as mapping kmers from the reads to a transcriptome-based de bruijn graph (exemplified by kallisto18 or ‘quasi-mapping’ of reads to transcript positions in a simple transcriptome-based index (e.g. Salmon19). These are normally followed by an expectation maximization (EM) step to resolve ambiguous assignments, re-proportioning reads based on evidence from the overall analysis. Estimates of read counts to the transcripts can then be generated and used in downstream analyses. For more background, a good independent summary of the ‘pseudo-alignment’ approach is found here. The EM step in particular has proven useful in finding additional genes or transcripts in data that were missed using alignment-based approaches, which normally skip ambiguously mapped sequences.

A key difference in these procedures from the alignment approach is the tools require a transcriptome data set (not a reference genome). This may be a problem if your reference genome annotation isn’t of reasonably high quality, for instance if the transcripts described aren’t well-annotated or incomplete. However, these tools are of great use for well-characterized genomes such as human and mouse, and can also be used with transcriptome assemblies.

Note, as these analyses generate estimated read counts as part of their output, you can skip Step 2.2

Step 2.2: Count generation

Protocol 1

Once it is determined that the alignment step was successful, the next step is to enumerate the number of reads that are associated with the genes. There are multiple tools to perform this step (e.g. HTSeq’s htseq-count24 , Subread’s featureCounts25 ), in addition, there are statistical analysis tools that do not require this step (e.g. Cufflinks’26 Cuffdiff and Ballgown). Both scenarios will be tackled in Phase III.

We recommend using featureCounts to collect the raw gene count information; this tool will require the alignment file (BAM), and the associated gene annotation file (GTF). Irrespective of the counting tool used, it needs the following information:

- Different sources have slightly different formats, so it is essential to specify how the counting needs to be performed, irrespective of the counting tool employed. Gene counts should be collected for each gene (

-gset as gene_id, forfeatureCounts), and at the level of the exon (-tset as exon, forfeatureCounts). - Are the data stranded, if so, was the standard dUTP method employed (

-sset as 2 for reverse, usingfeatureCounts)? - Different sources have slightly different formats, so it is essential to specify how the counting needs to be performed, irrespective of the counting tool employed. Gene counts should be collected for each gene (

-gset as gene_id, forfeatureCounts), and at the level of the exon (-tset as exon, forfeatureCounts). - Are the data stranded, if so, was the standard dUTP method employed (

-sset as 2 for reverse, usingfeatureCounts)?

The final output of any of these programs is a tab-delimited file with gene names in column one and counts in the second column. featureCounts will return an additional file that ends in .summary that specifies the number of reads that did not map only to one gene, split into various categories. It is normal for the total sum of all the rows in this file to be higher than the number of aligned reads for a sample, because if one read maps to two locations, featureCounts will count it twice in the Unassigned_MultiMapping category.

Protocol 2

Counts are already generated and can be skipped

Step 2.3: Collecting and tabulating alignment stats

Protocol 1

For a given RNA-Seq run it is valuable to collect several stats related to the alignment and counting steps; this is an important step in the evaluation process. There are many tools that gather this information from the SAM or BAM output file, e.g samtools’ flagstat27 , Picard’s CollectAlignmentSummaryMetrics28. However there are quirks with each reporting tool, hence it is recommended to collect this information as described in the table below.

| Gather numbers for the following categories | Calculating or gathering the information | Tool generating the information |

Total reads |

"Total Sequences" in the "Basic Statistics" section | FastQC |

Total reads after trimming |

"Total Sequences" in the "Basic Statistics" section (FastQC) OR "Number of input reads" in "Log.final.out" file (STAR) | FastQC OR STAR (prefix_Log.final.out) |

Unmapped reads |

Take the "Number of input reads" and subtract "Uniquely mapped reads number", "Number of reads mapped to multiple loci", and "Number of reads mapped to too many loci" | STAR (prefix_Log.final.out) |

Reads mapped to genome |

Add "Uniquely mapped reads number", "Number of reads mapped to multiple loci", and "Number of reads mapped to too many loci" | STAR (prefix_Log.final.out) |

Multiply mapped reads |

Add "Number of reads mapped to multiple loci", and "Number of reads mapped to too many loci" | STAR (prefix_Log.final.out) |

Reads mapped to genes |

This number is listed as "Assigned" in ".summary" file | featureCounts (prefix.txt.summary) |

Uniquely mapped reads without an associated gene |

This number is listed as "Unassigned_NoFeatures" in ".summary" file | featureCounts (prefix.txt.summary) |

Uniquely mapped reads with an ambiguous gene assignment |

This number is listed as "Unassigned_Ambiguity" in ".summary" file | featureCounts (prefix.txt.summary) |

You may also find it easier to collate all of the summary data from FastQC, STAR, featureCounts, and Picard’s metrics by running MultiQC on all of the reports generated by these three programs. MultiQC will generate an html file that visually summarizes this data as well as tab-delimited files containing all the stats produced by these programs.

Protocol 2

Apart from FASTQC, other standard QC metrics that rely on an alignment are not available, such as Picard’s tools, or a more complete assessment of read fates. Salmon and kallisto both provide output that give basic overall statistics such and the number of reads mapped, and MultiQC can also summarize this information for all samples.

Phase 3: Statistical analysis

Step 3.1: QC and outlier/batch detection

Alignment-based counts can normally be imported directly into R/Bioconductor29 , but estimated counts generated using Protocol 2 above will require importing using the tximport30 Bioconductor library. This can also be used to summarize transcript-level information to gene counts.

As mentioned above, estimated transcript-level counts can be used in standard differential gene expression analyses steps, but these should be imported using tools like tximport30 (for R/Bioconductor). We also recommend using these tools to sum transcript-level information to gene-level counts for initial analyses.

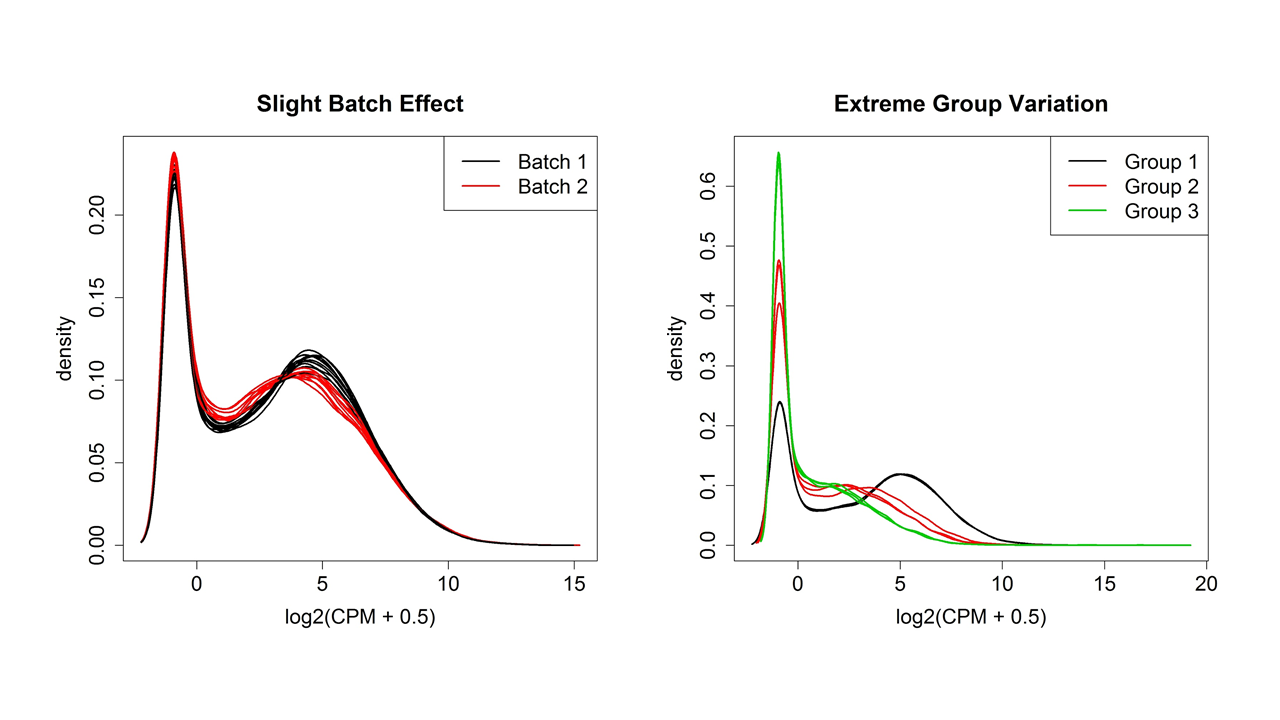

Once the counts have been generated, it is good practice to do some QC checks in addition to the ones listed above and to cluster the samples to see if there are any outliers or batch effects. Batch effects are usually caused by obtaining or processing the samples in batches and can obscure detection of expression differences if not adjust for statistically.

Figure 4 shows two examples of variation between samples plotted using the plotDensity function from the affy31 package in R (although the plotDensities function from the limma package32 is a newer choice). Whatever the shape of the distribution, ideally it will be about the same for all samples. One or two samples that are very different could be outliers, but if there are two or more distinct groups, see if they correspond to treatment groups or known or unknown batch effects.

There are other QC steps that are recommended, like simple hierarchical clustering (hclust + plot functions in base R) or Multidimensional Scaling clustering (plotMDS function in the limma package32). This will help validate the presence of outliers. Note that while StringTie33 has facilities for count generation, normalization and statistical analysis, it does not have any internal methods for sample QC or clustering. Instead, the R statistical software and add-on packages from Bioconductor29 are an excellent way to handle all aspects of statistical analysis of RNA-Seq data. They are free and available for any computer platform, although the command line interface can have a steep learning curve. Learning how to use R is well worth the time investment as it is a general tool for any sort of data manipulation, statistical analyses and graphing needs.

|

|---|

| Figure 4. Distributions of normalized expression values showing slight and extreme group/batch effects. |

Step 3.2: Remove low count genes and normalize

The QC investigations in Step 3.1 should be done on the output from htseq-count, which typically is the entire transcriptome (all genes). However, for most eukaryotic species, only ~40-60% of genes are expressed in any given cell, tissue or age and so a large proportion of the genes may contain 0 or only a few reads. It is recommended to remove these genes because they do not contain enough information to be statistically valid and it reduces the amount of multiple hypothesis testing (Step 3.3). A common practice is to require a minimum number of reads in a minimum number of samples. Often 1 CPM (count per million, relative to the total number of reads in the sample) is used as the minimum threshold but this may need to be adjusted up or down depending on the total number of reads per sample to get a threshold between 5 and 20 reads per gene.

The CPM adjustment is a minimal normalization that is necessary because of the normal large variation in total reads per sample. However, this assumes that the total number of reads should have been the same for all samples. This assumption can often be violated by extremely high expression in a few genes in one treatment or if the DE genes are predominantly in one direction. The traditional FPKM normalization used in older tools such as Cufflinks’ Cuffdiff cannot adjust for this and was one of the reasons FPKM was found to be inferior to other normalization methods, including Transcripts Per Million (or TPM34).

Which extra normalization, DESeq35 or TMM, to use in R depends on which package, DESeq236 or edgeR37, 38 , you prefer to use in R for statistical analysis. Both use extra normalization methods that are comparable and adjust for moderate biases in the number and direction of gene expression changes. Both are based on negative binomial statistical modeling and were found to compare quite evenly. Both have functions for outputting normalized expression values for use in QC and downstream visualizations. These normalized expression values should be put through the same QC metrics in Step 3.1 to see if the extra normalization rectified any problems indicated. Severe outliers should be removed and the data re-normalized. Remaining batch effects should be adjusted for in the statistical model.

Step 3.3: Statistics for differential expression

The main goal of most RNA-Seq is detection of differential expression between two or more groups. This is done for thousands of genes with often only a few replicates per group, so a statistical method must be used. This field is still under development and various statistical methods have been proposed. Both DESeq2 and edgeR can handle paired samples, other batch effects and complex designs. The choice between the two can simply be made based on which one is easier to understand and implement for the user.

In any statistical test of differential expression between groups, the amount of change from group to group must be evaluated by how much variation there is among the replicates of a group and how many replicates were used. These three factors, the amount of change, the amount of variation and the number of replicates are combined by the statistical test into one “p-value” which assesses the amount of evidence for differential expression. The traditional p-value cutoff of 0.05 for significance means that if you were to randomly sample two sets of replicates from the sample population 100 times, only 5 times would the value of the test statistic be larger than what you did see. This is a reasonable threshold when you only test a single gene, but in RNA-Seq you are measuring and testing thousands of genes at the same time. Therefore, some sort of adjustment of the p-values needs to be done. The most popular method is the False Discovery Rate method39 , which adjusts the p-values so that the entire set of genes with values less than 0.05 is expected to contain 5% false-positives. Depending on the goals of your experiment, the FDR p-value threshold can be raised to gain more true-positives at the expense of a higher false-positive rate. However, keep in mind that the FDR correction depends on how many genes have low p-values compared with the number expected to to have low p-values and the lack of any genes with reasonably low p-values does not mean that no genes were truly changing.

Working with Galaxy

If it is desirable to perform all processing in Galaxy40 , it should not be a problem for smaller experiments with a 1:1 comparisons between samples. For experiments with a large number of samples, and also for complex comparisons (e.g. 2x2 factorial design), Galaxy may not work as well; we instead recommend learning and using the command line tools and R/Bioconductor. However, Galaxy can be used to test parameter settings on a subset of the data, prior to switching over to command line for the whole analysis. Another issue of note, though Galaxy is quite good with data provenance,the latest versions of tools may not be available in Galaxy’s Tool Shed (in particular those available in R/Bioconductor); In most cases Galaxy’s excellent data provenance tracking will keep track of the versions used, so please make a note of the version numbers.

The Galaxy Tool Shed lists all tools currently available through Galaxy. Tools available in Galaxy mentioned above include:

- FASTQC

- STAR

- featureCounts

- Trimmomatic, Trim_galore

- Picard

- edgeR, DESeq2

- Kallisto

- Salmon

H3ABioNet Accreditation exercise

Practice dataset

Some practice dataset for RNA seq analysis can be found here

A. Reproducible Research

In any experiment where computation plays a critical role in generating the results and conclusions, researchers should ensure that the presentation of their work includes reproducibility, meaning “the ability to recompute data analytic results given an observed dataset and knowledge of the data analysis pipeline.”41. This is distinct from the concept of replicability, in which “the chance that an independent experiment targeting the same scientific question will produce a consistent result”41.

For a RNA-Seq experiment, reproducible means documenting in detail all the steps taken from the original fastq files through the end of the statistical analysis and any downstream data mining. The reasons to do this are multifold, three of which are: 1) so reviewers can assess whether the computational steps are valid and match what was described in the report, 2) to serve as a record for your lab, a “computational” notebook equivalent to the laboratory notebook and 3) to serve as a teaching guide for colleagues to use in other experiments42 (see Introduction). The typical Methods section allowed in a publication only gives a brief description of the steps taken and is not sufficient for reproducibility. Instead, the documentation for reproducibility can go into supplementary files and typically includes codes for software calls and parameters, statistical analysis and generation of figures and tables for the publication. Advanced users can create versioned-controlled Rmarkdown-type documents that integrate codes with figures, graphs and written explanations42 (see Tools) but simple README.txt and AnalysisCodes.R files can also suffice. Beware to limit the manual manipulation of intermediate files, which is difficult to describe and hence difficult to reproduce. Instead, the output files from one section should be the input files for the next section, or else manually-created files should be put in the supplemental as well.

Finally, note that reproducible research documentation is addition to, and not a replacement for, the written report that describes the reasons behind the selected choices and synthesizes the overall understanding and issues involved in RNA-Seq analysis.

For more information and guidance, see:

- Leek & Peng 201541

- rOpenSci’s Reproducibilty Guide42

- Peng 201143

- Peng 2014 blog post at SimplyStatistics.org

B. General questions

These questions, originally derived for the 16S analysis, relate to other sequencing workflows as well.

Questions related to the nature of the input sequence data

- Were the number, length and quality of the reads obtained in line with what would be expected for the sequencing platform used?

- Was the input dataset of sufficiently good quality to perform the analysis?

- How did the reads’ quality and GC content affect the way analysis was run?

Operational questions

- At each step of the workflow, describe which software was used and why:

- Was the choice affected by the nature and/or quality of the reads?

- Was the choice made due to the time and cost of the analysis?

- What are the accuracy and performance considerations for the chosen piece of software?

- For each software, describe which input parameters were chosen, and why:

- Was the choice affected by the nature and/or quality of the reads?

- Did the available hardware play a role in the parameter choice?

- How did the purpose of the study affect the parameter choice?

- For each step of the workflow, how do you know that it completed successfully and that the results are usable for the next step?

Runtime analysis

This is useful information for making predictions for the clients and collaborators

- How much time, memory, and disk space did each step of the workflow take?

- How did the underlying hardware perform?

- Was it possible to do other things, or run other analyses on the same computer at the same time?

C. Analysis-specific questions

The following questions relate specifically to the phases denoted above.

PHASE 1 - Preprocessing of the raw reads

- What percentage of the reads were removed during the quality trimming step?

- Did all samples have similar number of reads after the preprocessing of reads steps?

- What tools were used for assessing quality of the reads?

PHASE 2 - Determining how many read counts are associated with known genes

Alignment and generation of gene/transcript counts

- What percentage of the reads aligned to the genome sequence? If the data are paired-end, how many of the reads are aligning in a concordant manner?

- How many reads mapped within exons? In introns? Intergenic regions? Are these consistent across samples? What do the relative proportions of reads in each region tell you about your samples?

- What tools/methods were used to determine this?

Pseudoalignment-based methods

- What percentage of the reads mapped successfully to transcripts? Are these consistent across samples? How is this information similar to / different from what you get from genome alignment?

- What are the different quantification values you can get from the pseudo-alignment methods? Which one did you decide to use and why?

- How do counts between the two methods (alignment vs. pseudoalignment) compare?

PHASE 3 - Initial differential gene expression analysis

- Describe the normalization methods used for both statistical analysis and visualizations and why the methods were selected.

- During the initial stages of analysis, do experimental samples cluster as expected i.e. based on the experimental conditions? What other information can be gained from sample clustering?

- Which statistical methods and options did you pick and why?

- Which filtering method/s did you use for filtering out the low expressed genes/ transcripts?

- What would be the next steps for your analysis, given the results of Phase 3?

Questions on additional analyses

Additional downstream tertiary analyses are very commonly performed using RNA-Seq data, for example gene set enrichment, isoform analysis, surrogate variables analysis, or weighted gene coexpression network analysis. As these are highly dependent on the data available and the results (particularly from differential expression analysis), we do not cover them in detail, and thus these are not currently part of the accreditation exercise.

Nodes are more than welcome to attempt these, however. Should these be attempted, the following questions (though not comprehensive) may help guide what is expected regarding reporting of results.

- Alternative reference genomes - How does changing the reference genome and annotation used influence your final results, choice of software, and parameters?

- Isoform analysis - What method/s did you use for the identification of alternative splicing and why? Provide splice variants with list of exons associated with each isoform.

- Pathway annotation source - Where did you get additional annotation information on the genes (i.e., gene names, symbols, GO (Gene Ontology)44 terms, KEGG45 pathways) and when was that resource last updated?

- General pathway analyses - What is the impact of the experiment on biological pathways and processes?, i.e. how many Gene Ontology (GO) terms were found to be over-represented within differentially expressed genes?

- Assessing for unknown signals in analyses - Were methods used to adjust for potentially unknown factors in your analysis, such as unknown confounding variables? If so, how did this influence your results?

Bibliography

-

Robinson, Mark D., and Alicia Oshlack. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome biology 11.3 (2010): R25. ↩

-

Trapnell, C., Roberts, A., Goff, L., Pertea, G., Kim, D., Kelley, D. R., … & Pachter, L. (2012). Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nature protocols, 7(3), 562. ↩

-

Love MI, Anders S, Kim V and Huber W. RNA-Seq workflow: gene-level exploratory analysis and differential expression. F1000Research 2016, 4:1070. ↩

-

Law CW, Alhamdoosh M, Su S et al. RNA-seq analysis is easy as 1-2-3 with limma, Glimma and edgeR. F1000Research 2018, 5:1408. ↩

-

Conesa, A., Madrigal, P., Tarazona S., … & Mortazavi, A. 2016. A survey of best practices for RNA-Seq data analysis. Genome Biology 17:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-0881-8 ↩

-

Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P., & Pachter, L. (2016). Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nature biotechnology, 34(5), 525. ↩

-

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A., & Kingsford, C. (2017). Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nature methods, 14(4), 417. ↩

-

Andrews, S. (2010). FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. ↩

-

Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Lundin, S., & Käller, M. (2016). MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics, 32(19), 3047-3048. ↩

-

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M., & Usadel, B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics, 30(15), 2114-2120. ↩

-

Dodt, M., Roehr, J. T., Ahmed, R., & Dieterich, C. (2012). FLEXBAR—flexible barcode and adapter processing for next-generation sequencing platforms. ↩

-

Gordon, A., & Hannon, G. (2010). Fastx-toolkit. FASTQ/A short-reads pre-processing tools. Unpublished ↩

-

(PRINSEQ) Schmieder, R., & Edwards, R. (2011). Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics, 27(6), 863-864. ↩ ↩2

-

Cox, M. P., Peterson, D. A., & Biggs, P. J. (2010). SolexaQA: At-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. BMC bioinformatics, 11(1), 485. ↩

-

Patro, R., Mount, S. M., & Kingsford, C. (2014). Sailfish enables alignment-free isoform quantification from RNA-seq reads using lightweight algorithms. Nature biotechnology, 32(5), 462. ↩

-

Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P., & Pachter, L. (2016). Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nature biotechnology, 34(5), 525. ↩ ↩2

-

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A., & Kingsford, C. (2017). Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nature methods, 14(4), 417. ↩ ↩2

-

Dobin, A., Davis, C. A., Schlesinger, F., Drenkow, J., Zaleski, C., Jha, S., … & Gingeras, T. R. (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics, 29(1), 15-21. ↩

-

Kim, D., Langmead, B., & Salzberg, S. L. (2015). HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nature methods, 12(4), 357. ↩

-

Wu, T. D., & Nacu, S. (2010). Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics, 26(7), 873-881. ↩

-

Huang, S., Zhang, J., Li, R., Zhang, W., He, Z., Lam, T. W., … & Yiu, S. M. (2011). SOAPsplice: genome-wide ab initio detection of splice junctions from RNA-Seq data. Frontiers in genetics, 2, 46. ↩

-

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T., & Huber, W. (2015). HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics, 31(2), 166-169. ↩

-

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K., & Shi, W. (2013). featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics, 30(7), 923-930. ↩

-

(Cufflinks) Trapnell, C., Williams, B. A., Pertea, G., Mortazavi, A., Kwan, G., Van Baren, M. J., … & Pachter, L. (2010). Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature biotechnology, 28(5), 511. ↩

-

Li, H., Handsaker, B., Wysoker, A., Fennell, T., Ruan, J., Homer, N., … & Durbin, R. (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics, 25(16), 2078-2079. ↩

-

Gentleman, R. C., Carey, V. J., Bates, D. M., Bolstad, B., Dettling, M., Dudoit, S., … & Hornik, K. (2004). Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome biology, 5(10), R80. ↩ ↩2

-

Soneson, C., Love, M. I., & Robinson, M. D. (2015). Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Research, 4. ↩ ↩2

-

Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA (2004). affy—analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics, 20(3), 307–315. ISSN 1367-4803, ↩

-

Ritchie, ME, Phipson, B, Wu, D, Hu, Y, Law, CW, Shi, W, and Smyth, GK (2015). limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Research 43(7), e47. ↩ ↩2

-

Pertea, M., Pertea, G. M., Antonescu, C. M., Chang, T. C., Mendell, J. T., & Salzberg, S. L. (2015). StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature biotechnology, 33(3), 290. ↩

-

Dillies, M. A., Rau, A., Aubert, J., Hennequet-Antier, C., Jeanmougin, M., Servant, N., … & Guernec, G. (2013). A comprehensive evaluation of normalization methods for Illumina high-throughput RNA sequencing data analysis. Briefings in bioinformatics, 14(6), 671-683. ↩

-

Anders S, Huber W (2010). Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biology, 11, R106. ↩

-

Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology, 15, 550. ↩

-

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010). edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics, 26(1), 139-140. ↩

-

McCarthy, J. D, Chen, Yunshun, Smyth, K. G (2012). Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Research, 40(10), 4288-4297. ↩

-

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the royal statistical society. Series B (Methodological), 289-300. ↩

-

Afgan, E., Baker, D., Batut, B., Van Den Beek, M., Bouvier, D., Čech, M., … & Guerler, A. (2018). The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2018 update. Nucleic acids research, 46(W1), W537-W544. ↩

-

Leek, J.T., & Peng, R. D. (2015). Reproducible research can still be wrong. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (6) 1645-1646 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Reproducibility in Science: A Guide to enhancing reproducibility in scientific results and writing. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Peng, R. D. (2011). Reproducible Research in Computational Science. Science Vol. 334, Issue 6060, pp. 1226-1227. ↩

-

Ashburner, M., Ball, C. A., Blake, J. A., Botstein, D., Butler, H., Cherry, J. M., … & Harris, M. A. (2000). Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature genetics, 25(1), 25. ↩

-

Kanehisa, M., & Goto, S. (2000). KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic acids research, 28(1), 27-30. ↩

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.